Suggested route to the stopping point.

The sediments that make up Illa d’en Colom were deposited around 350 million years ago at great sea depths by turbulent currents that began on the continental shelf and that over time formed successive layers of sandstones and lloselles. Of particular interest is the tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop that you can see in a corner between the Cap de Mestral headland and Sa Mitja Lluna, which is the reason for stopping here. Here, the cliff comprises a series of layers of black sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella on top of which there is another series of brownish sand-sized clasts.</p><p><br></p></div>">sandstone where the grains of sand make it rather coarse-grained. The contact between the two is very clean and clear.

Contact between the coarse-grained, brownish sandstone and the black llosella below, near Cap de Mestral point. Despite its massive appearance, if you look closely, the layers of sandstone are interleaved with very thin layers of llosella. The same occurs with the strata underneath, inside which layers of fine-grained sandstone can be identified (point A).

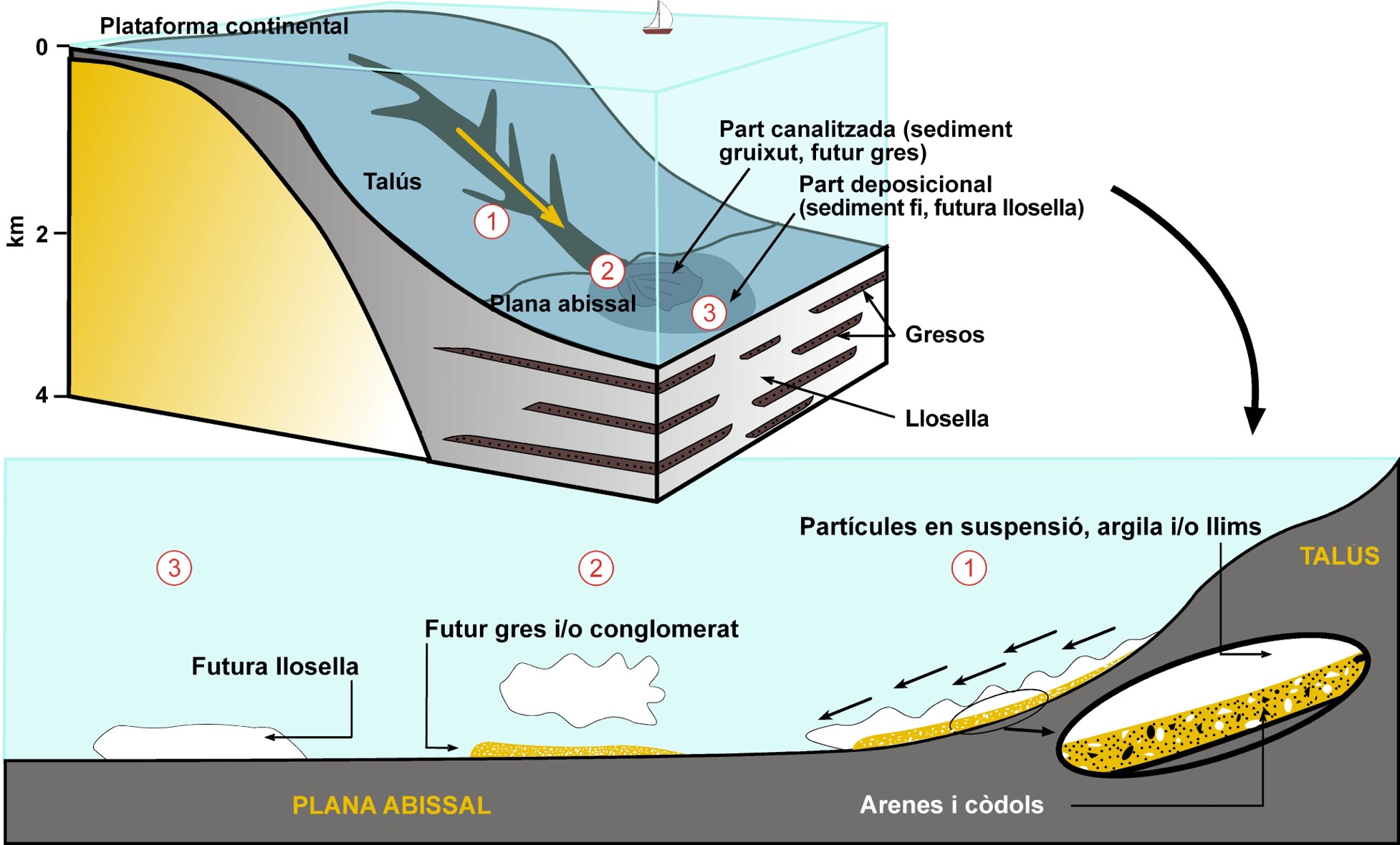

A great flooding of a river whose mouth is close to the start of an underwater canyon may cause sediments to drop suddenly to the great sea depths. Even a slight earthquake may cause a mass fall of sediments deposited originally on the continental shelf near the talus and, therefore, some instability. In both cases, the sediments fall very quickly taking advantage of the slope of the underwater canyon or of the talus in the form of a turbulent current, creating an avalanche of different types of sediments and water that accelerate as they fall downwards while separating from the seawater as a current of turbulent water.

When the sediments reach the abyssal plain, they start to slow down and the turbulent current gradually releases the sedimentary fractions as it no longer has the strength to keep them in suspension, in other words, it can no longer transport them. Consequently, it will first deposit the thicker particles and then the finer ones. Here, the sediments form an underwater delta of similar characteristics to one you would find in a river. On the delta that has developed at great sea depths, differentiation should be made between a grooved part closer to the talus and another further away or distal, depositional part. In the grooved part, currents travel confined to the depressions forming the channels. When the channel ends, the currents stop, as they cannot transport the material any further and they deposit it quickly. Due to its volume, when the turbulent current overflows, it invades a larger space than the channels and sediments the finer materials more slowly in a process that may take a day.

Over time, the particles that are thicker than the size of sand will form a rock that we call sand-sized clasts.</p><p><br></p></div>">sandstone, which you can see at the top of the tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop and that is from the sand that was dragged by the channels, while the finer ones will form the sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella that you can see below. We should point out that both types of rock correspond to different episodes of flooding over time, so that when the sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella below sedimented, sandstones that we cannot see here sedimented in an area nearer the talus. The same occurred when the sand that caused the sandstones at the top of the tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop did so; a finer sediment that accompanied the turbulent current was deposited further away.

The ocean depths are made up of three parts: the continental shelf, with depths of less than 200 metres and near the coast; the abyssal plain, at the great sea depths with a huge extent found kilometres deep; and the slope or talus, a large sloping step that joins the two. Masses of sediments can break off from the shelf and travel as a turbulent current that descends the slope at great speed (1). When it reaches the abyssal plain, the turbulent current slows down and causes sedimentation of the thick particles first (sand and cobbles), with the finer particles still in suspension (clay and silts) (2); subsequently, sedimentation of the fine particles occurs (3). Over time, the thick particles form conglomerates and sandstones while the fine particles form lloselles.

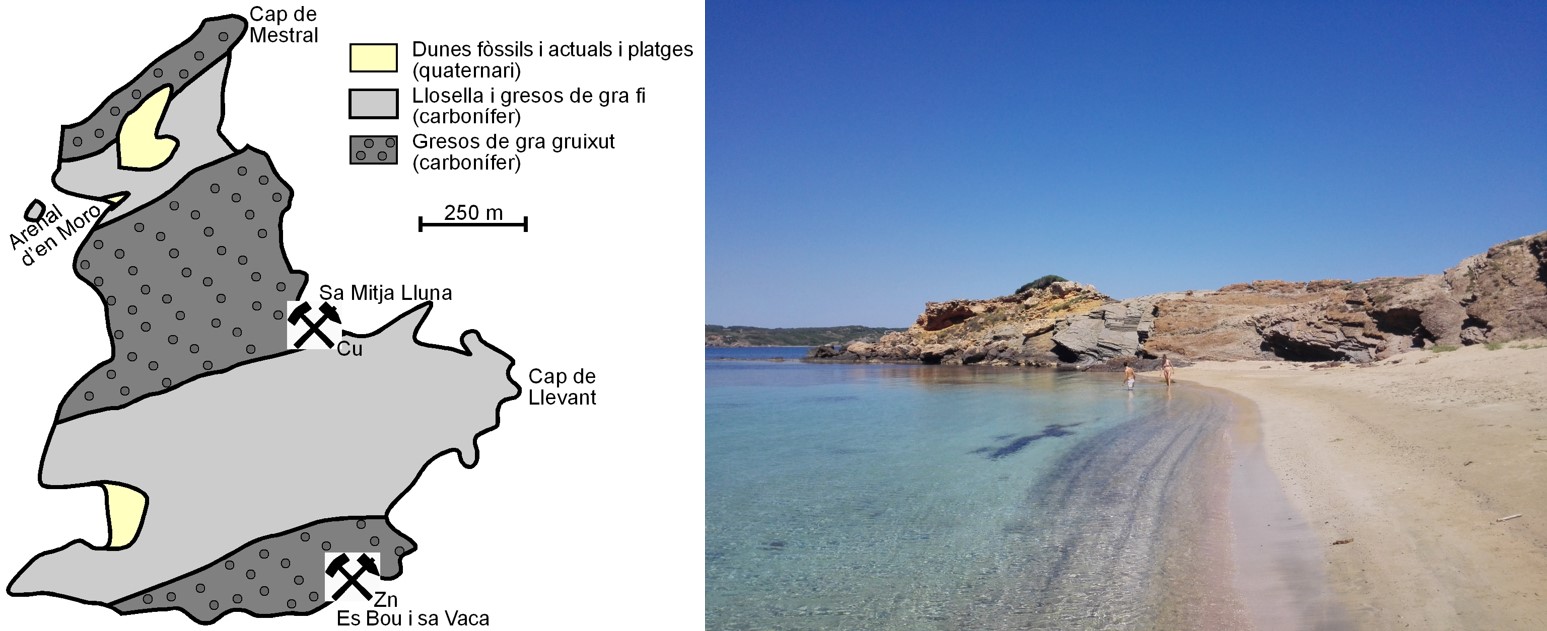

If you carry on the route towards the Arenal d’en Moro sandy beach, passing the islet’s Cap de Mestral point, you will see that its northern end is made up of thick layers of sandstones, which are strong and resistant to erosion. This factor determines the coastal landscape of a large part of the nature reserve. Soft rocks such as sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella are easy to erode by the effect of the waves, especially conditioned by the Tramuntana storms, salt and wind, but also by rainwater. Where these rocks are found, over thousands of years, coves and inlets have been formed. Hard rocks such as sandstones form promontories and islets.

When you reach the Arenal d’en Moro sandy beach, you will be able to see this for yourself. The cove has opened up in the sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella due to the effect of the waves and also to the action of a small stream that has carved out these soft rocks that you can see without any problems on the northern edge of the beach. By contrast, in the south of the cove, you can see thick layers that make a breakwater, which also protect the sand from being washed away. These are the rocks you have just seen when you came round the islet from the northern side. In other words, the beach has been opened up due to the action of erosive agents on soft rocks, but it lies between two levels of resistant sandstones that protect it and prevent the waves from dragging the sand away.

This alternation of sandstones and sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella is the same as you have seen at the start of the stopping point with the same layout, although it might not seem like that; near Cap de Mestral you can see the sandstones superimposed on the lloselles, while at the Arenal d’en Moro sandy beach, the sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella has been eroded quite a lot, creating the beach.

Coarse-grained sandstones on the north of the islet, resistant to the battering of the waves, between which fine layers of llosella are interleaved (point B).

Geological map of Illa d’en Colom (with the location of the two mines). The Arenal d’en Moro sandy beach was excavated in soft materials such as sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella, but on its south side, you can see coarse-grained sandstones that protect the sand from the battering of the waves and partly stop them from washing it away. You have also seen these coarse sandstones when you came around the north of the islet and at the entrance to the south of Cap de Mestral, where you can see the same level of sandstones as the beach on top of the sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella. The extensive slabs of this sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella can be seen on the northern edge of the Arenal d’en Moro sandy beach (point C) (simplified map by Rosell, J., Gómez-Gras, D. & Elízaga, E. 1989. Geological map of Spain, scale 1:25.000. Page no. 647, IV (Maó – Illa d’en Colom). Spanish Geological Survey. Madrid).

The weathering of the rocks causes the cement that binds the grains of sand forming the sandstones to disappear, meaning that they end up in the sea, and the waves subsequently accumulate them on beaches such as the Arenal d’en Moro sandy beach. This is why the sand on this beach is coarse. However, it should be remembered that 78.4% of the components of the sands on the beaches in Menorca (71.3% with regard to the beaches in the north of the island) are fragments of calcareous skeletons of marine organisms, such as clams, snails, Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">limestone algae, foraminifera, bryozoa, etc. For this reason, the presence of Posidonia oceanica (Neptune grass, an aquatic plant endemic to the Mediterranean of very important ecological importance) represents a key role in bringing in new sand, as it produces oxygen and organic matter needed for the life of many living beings, which will directly or indirectly contribute to the formation of most of the sand.