| UTM-X | UTM-Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STOP 1: EN VERMELL | |||

| STOP 2: LLOSA DE RAFALET | |||

| STOP 3: PUNTA DES FALCONS | |||

| STOP 4: ILLOT DES TORN AND CALÓ ROIG | |||

| STOP 5: TORRE D’ALCALFAR |

Access route to the stopping point and continuation towards the next one.

The stopping point centres on an interesting tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop to the south of the Llosa de Rafalet, of the same characteristics as the last observation point at En Vermell, but in this case with a greater continuity and better development. At this tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop, the rock is carpeted by a rather spectacular crust of golden or ochre colourations.

This crust marks the boundary between the two upper units into which the Migjorn region of Menorca is divided. Marès, the predominant rock in the region, is made up of fragments of shells of marine organisms together with sediments from the dismantling of the relief that formed the Tramuntana region in the Miocene. In any event, it should be remembered that its composition varies depending to a large extent on the time when the rock was formed, under one climate or another, and the place where it was formed, for example depending on the depth, as logically, depending on these two factors, the remains of the living beings that would end up constituting a large part of the rock would be different.

These differences allow us to identify three geological units in the Migjorn region of Menorca, each one with its own peculiarities. The lowest and oldest, which is, in turn, the least important in terms of extent, is a unit made up essentially of conglomerates sedimented in the lower and/or middle Miocene (around 15 million years ago) and can be identified clearly at Cala Morell. The middle was deposited later, in the lower Tortonian (now in the upper Miocene, some 11 million years ago), and dominates most of this region of the island. It is made up primarily of marès, although we do see other rocks, such as the sandstones and conglomerates of En Vermell, and was sedimented in a flat and inclined area towards the sea depths, at different depths, where numerous and varied life forms proliferated. Above, the most recent unit is attributed to the upper Tortonian – Messinian (also in the upper Miocene, but sedimented around 7 million years ago) and is made up of both limestones (living rock) and marès formed under a reef environment, so this unit is also known as a Reef unit.

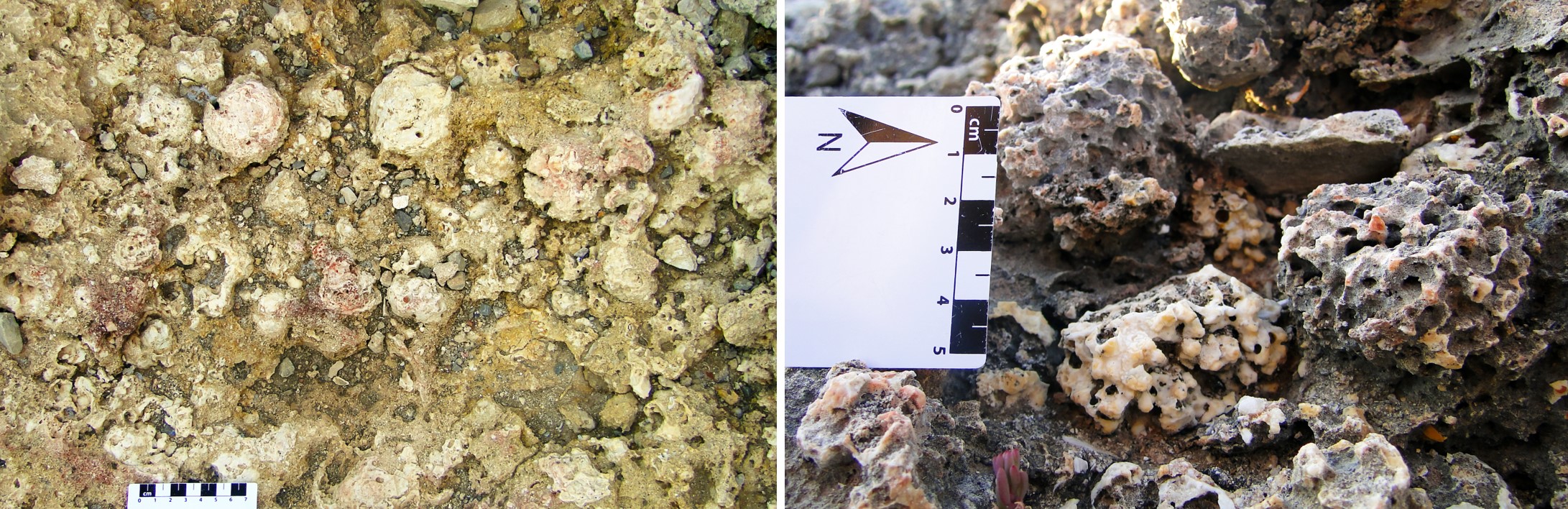

Of an ochreish tone and made up mainly of phosphate, the crust that the stopping point focuses on marks the change between the middle and upper units. It can be related to the surface of a seabed made up of a very hard layer encrusted with phosphate (among other more scarce elements such as iron). For them to form, the interruption of sedimentation for a long time is needed, so the top part of the existing sediments hardens, creating a hardened marine surface known as ‘bentonic communities tend to settle. It is indicative of long periods of little or no sedimentation, or of the exposure of a lithified stratum after an erosive period followed by an inundation.</p><p class="ql-align-justify"><br></p></div>">hardground’. The causes of this stoppage can be very diverse, for example, it could be due to the action of sea currents preventing the deposition of sediments. The crusts often contain unique fauna adapted to the hard surface. At S’Algar, we can discern the fossils of large clams.

Hardground or phosphate crust at Llosa de Rafalet that separates (marked in red) the middle (UIB) and upper (UE) geological units into which the Migjorn region of Menorca is divided (point A).

Fossils of large clams embedded in the crust (point A).

Underneath the crust, and therefore the last sediments of the middle unit, you can see abundant fossils of red algae (rhodoliths) that constitute nodules. Rhodoliths are nodules of algae made up primarily of coral algae that grow around the remains of a solid, such as a cobble or a shell fragment. Since algae need light to grow, they always develop in the area between the surface of the sea water and the shallows, known as the photic zone, from which point on photosynthesis is not possible as there is insufficient sunlight.

These algae are characterised by the fact that they can incorporate calcium carbonate into their tissues, in other words, they calcify, making it easy for them to become fossilised. As they grow, most of these types of algae become somewhat spherical due to the dynamics of the environment caused by the movement they are subjected to from the currents and waves. In other words, the tumbling they are subjected to by the movement of the seawater where they live gives them this shape. Despite this, their external morphology may vary, among other shapes, from spherical to more or less flat.

Red algae nodules (rhodoliths) and close-up of them in the layer situated just underneath the crust (point A).

Immediately above the crust, and consequently in the sediments of the upper or reef unit, you can see fossils of irregular sea urchins with a thick shell and slightly flared shape (Clypeaster sp) as well as clams.

The middle unit at S’Algar was sedimented between 15 and 20 metres in depth. The upper one would have done this at a much greater depth, in the lower part of the photic zone, which, in any event, had to be less than around a hundred metres and, as we have said, in an atmosphere dominated by reefs.

The change in sedimentation, which the passage from one unit to the other entails, is related to a variation in the ecological conditions, which, possibly linked to a rise in temperature (caused by a climate change that went from wet to dry) meant a decrease in nutrients and, therefore, an alteration in the food chain. The decrease in nutrients in the water was an essential factor that enabled the development of the reef complex as it needed these to grow an atmosphere of clean, clear and sunny waters.