| UTM-X | UTM-Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STOP 1: EN VERMELL | |||

| STOP 2: LLOSA DE RAFALET | |||

| STOP 3: PUNTA DES FALCONS | |||

| STOP 4: ILLOT DES TORN AND CALÓ ROIG | |||

| STOP 5: TORRE D’ALCALFAR |

Proposed route to the stopping point.

The observation points on the trail pick up again on the other side of the Passeig Marítim promenade near the swimming pool of a hotel complex. The phosphate crust outcrops again here. In fact, we could have followed the crust along the whole of the Passeig Marítim, but the hotel was built, along with others, on top of the layer containing the crust, so covering it.

We should point out that the passing from one unit to another, marked by the presence of the crust, is rather exceptional on the island, as it is only observed in this area. Consequently, the passing from the middle unit to the upper unit is usually related to a layer crammed with small fossils of foraminifera known as ‘Heterostegina’, which can be recognised, for example, at Cala en Blanes, as well as other sites.

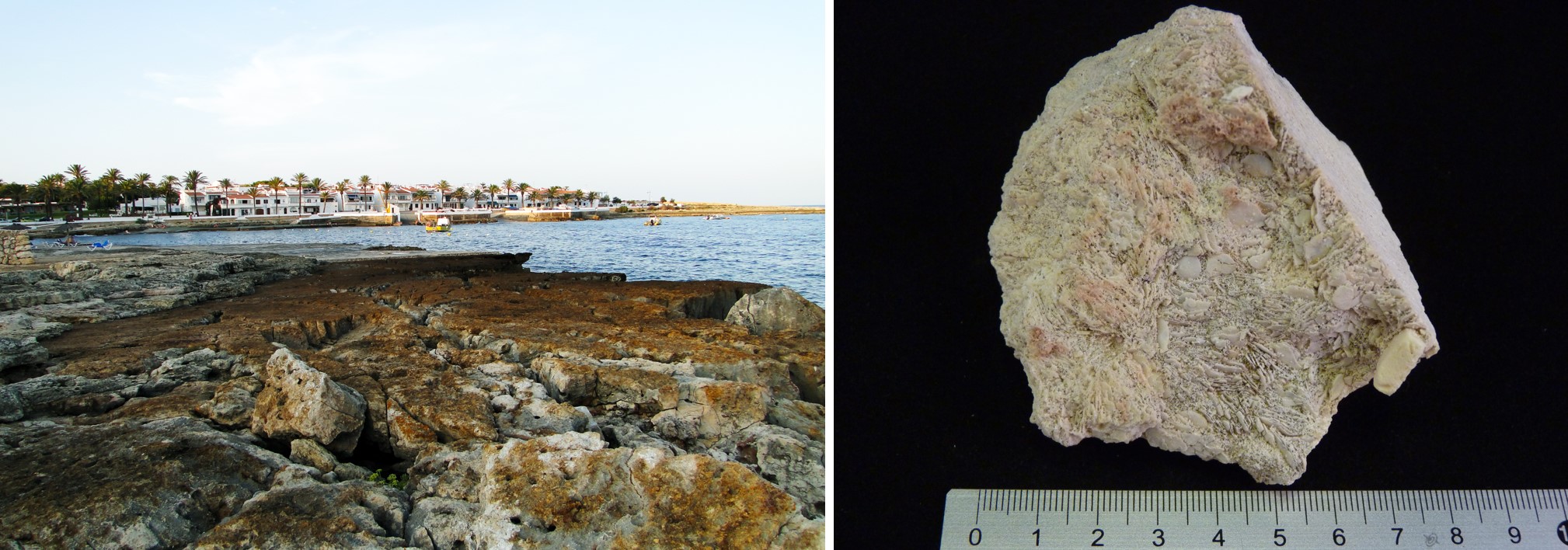

Phosphate crust at the stopping point (point A) and rock with Heterostegina gathered in a rock layer in Cala en Blanes. The presence of these layers mark a change in the type of sedimentation in the Migjorn region of Menorca, which implies the start of the development of a sedimentary atmosphere dominated by reefs.

The stopping point allows you to identify some of the characteristics of the upper or reef unit positioned on top of the crust. Consequently, you can identify fossils of sea urchins, large rhodoliths, clams and brachiopods, marine animals with a shell made up of two valves like clams, but articulated differently, which differentiates them from clams. In fact, rhodoliths, sea urchins and clams are the most frequently found fossils in the rocks of the Migjorn region of Menorca, which must lead us to deduce that they were very common living beings in the sea when the rock was formed.

Fossils at the stopping point of sea urchins (Clypeaster sp., large, bell-shaped with thick walls) (point A), red algae (rhodoliths) and clams (pectinids) (point B).

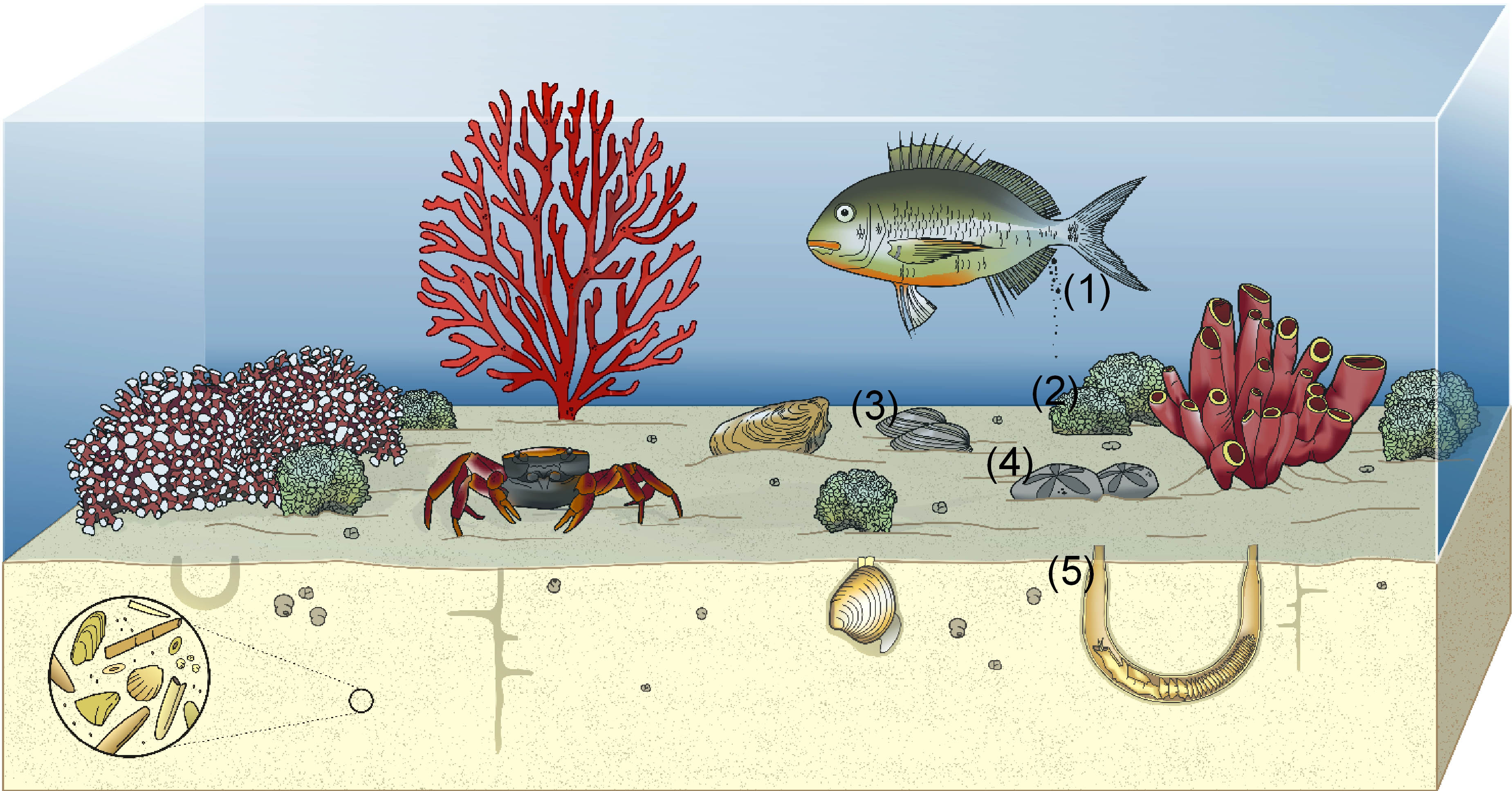

Marès is a sandy rock made up largely of skeletons and shells of organisms that have been broken by the currents, waves or by other organisms such as fish (1). Occasionally, the hard parts of these living beings were not broken and were able to fossilise, which enables us to know which living beings inhabited the sea around Menorca when these rocks were formed and, due to their abundance, which ones dominated. This would be the case of the red algae or rhodoliths (2), clams (3) and irregular sea urchins (4). Frequently, these sediments are shaken up by the action of organisms that excavated galleries, which have been preserved until today (5).

One of the features that is most striking at the stopping point are the rocks that make up the layers are quite altered, displaying a large network of more or less bifurcated and branched tubes, which are galleries that were excavated by crabs. In the sand that would end up forming the rock, numerous crabs lived, excavating fairly complex galleries. Over time, and after they had been abandoned, the galleries were refilled with a different sand from the rock containing them, which means they stand out and can be identified clearly. Consequently, in their desire to find food, shelter or escape their predators and enemies, the crabs stirred up the sediment, which would later consolidate forming a rock and creating these shapes that we associate with the process known as ‘bioturbation’ or ‘bioerosion’, erosion associated with living beings.

Surface of a completely bioturbated stratum with numerous galleries. The tubes stand proud of the rock as they were eroded differently (point C).

In the section of the coast between the residential areas of S’Algar and Alcalfar, you can see blocks that are large pieces of strata that were dragged and carried in from the sea by the waves as though they were huge cobbles and deposited on dry land. Bearing in mind that this coast is very much affected by storms from the east, this accumulation of blocks has been associated with large storms or even tsunamis.

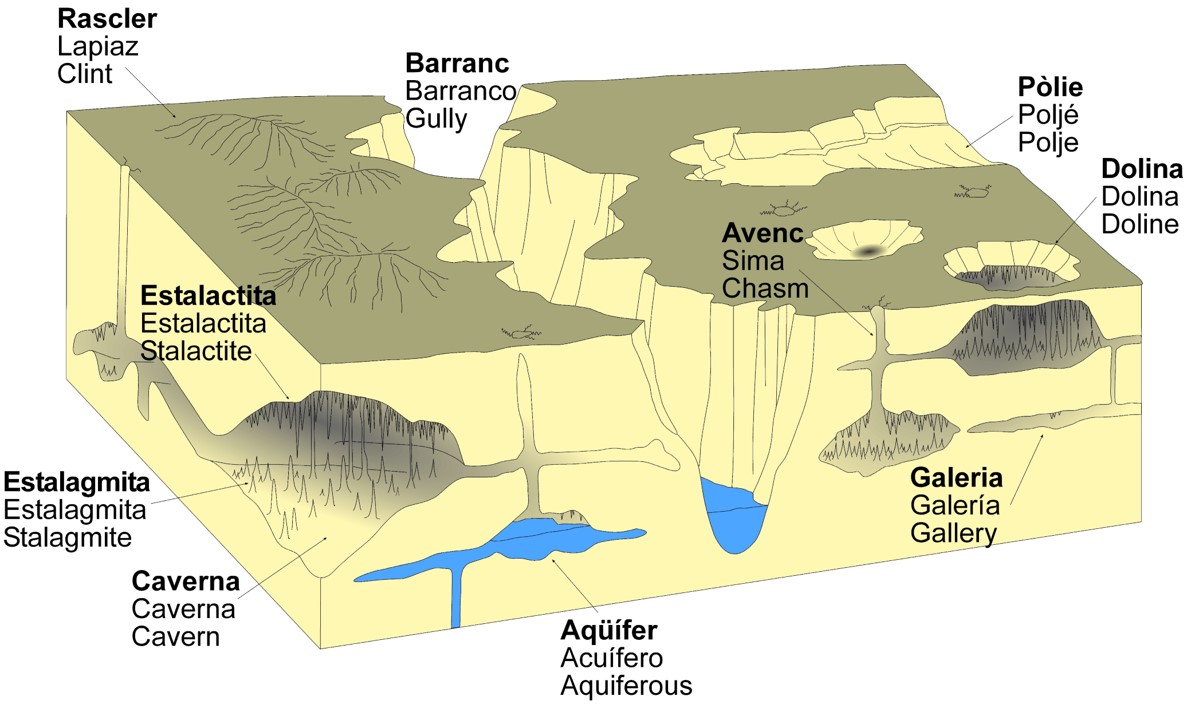

The rocks in this part of the coast are intensely eroded, both on the surface and, especially, underground. The erosion is caused above all by the dissolving of waters heavy with CO2 in the karstification process, which was mentioned at the first stopping point. Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">Limestone rocks are not water-soluble, but they dissolve very easily in waters that have small amounts of carbonic acid, as is the case of underground water. Carbonic acid is formed because rainwater easily dissolves the carbon dioxide in the air and from plant decomposition. So, when underground water comes into contact with limestones, the carbonic acid reacts with the carbonate in the rocks to form calcium bicarbonate, which dissolves quickly and easily in water.

On the surface of the ground, as a result of this karstification process, the rocks take on peculiar shapes that lead to fields of rectilinear or curving troughs and sharpened peaks called ‘clints’ or ‘lapies’. This process can form incisions of a few metres, but in Menorca the clints are much smaller, so we can regard it as a process that is not displayed intensely but that is very present, creating very uneven ground in the Migjorn region that is uncomfortable to move across.

Karst landscape resulting from the erosion of the Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">limestone rocks. Karst is the same type of erosion that creates large ravines excavated by the streams that flowed into the sea on the south coast of the island or that creates galleries, chasms and caves underground. This type of erosion means that the subsoil in the south of Menorca is completely perforated; in fact, karst erosion is a fundamental element in the existence of the most important aquifer on the island in the rocks of the Migjorn region of Menorca.

Near the Punta des Falcons headland, you can see caves with large openings right on the sea, which are very common along the whole of the southern coast. They are formed to a large extent by the interaction between the dissolving of underground fresh water and salty sea water, which also penetrates the rock, besides causing mechanical erosion through the battering of the waves. The mix of the two waters, of quite different chemical compositions, means that they become much more aggressive and so increase the dissolving of the rock with the creation of large cavities. The dissolving of the rocks will end up enlarging the caves to the point where they can no longer bear the weight of the land on top of them and they collapse. At the stopping point, you can see the presence of a large coastal cave covered by a few thin layers of rock. The evolution of the erosion process will, over time, mean that the roof of the cave (the layers you can see) may fall in. The falling of rocks from the cliffs leads to their retreating, and this is to a large extent the cause of the formation of the coves in the south of Menorca.

Cova d’en Melià cave near Punta des Falcons headland with a quite thin wall. In the surrounding area (close-up in the photograph on the right), the ground is rather uneven due to the presence of clints (point D).