| UTM-X | UTM-Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STOP 1: PUNTA ROJA HEADLAND | |||

| STOP 2: LA VALL BELVEDERE | |||

| STOP 3: CALA FONTANELLES | |||

| STOP 4: CODOLAR DE BINIATRAM |

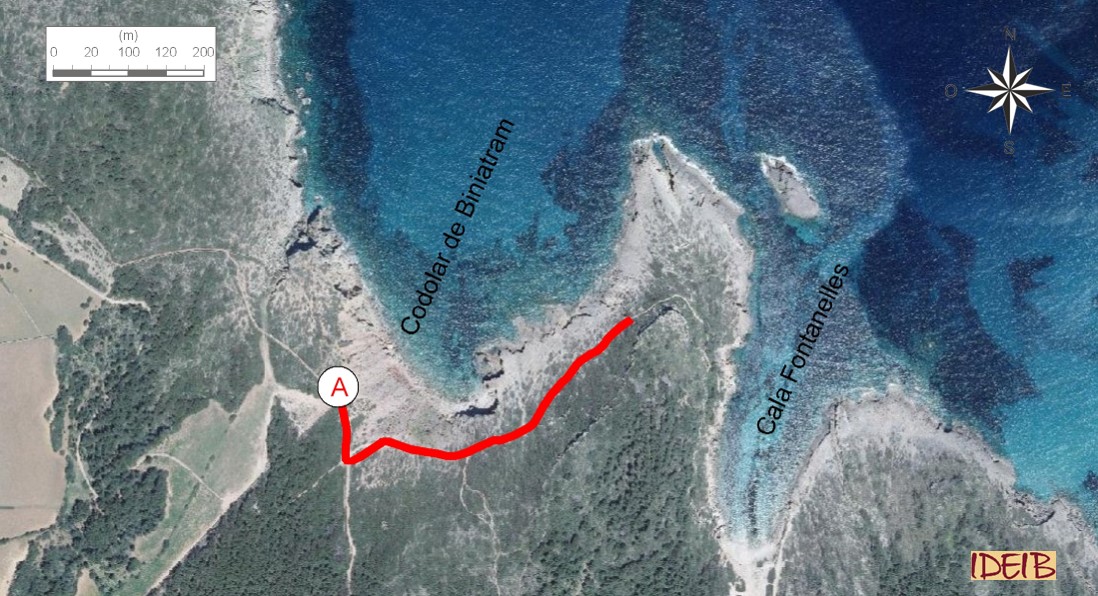

Access to the stopping point.

As you get near the red rocks at the Codolar de Biniatram pebble beach, you can see rocks from the Quaternary again. This stretch of coast allows us to determine that these rocks were formed at different times. The rocks nearest the sea are softer than the ones in the rock step that you can see at the top of the cliff, above the path, which has a more compact appearance. This difference is due primarily to time. The rocks at the top are older than the ones at the bottom and have had more time to consolidate, so the ones nearer the sea were formed thousands of years later. The dunes at the rock step are the same as the ones that make up the western side of Cala Fontanelles, responsible for the presence of a spring. All of these rocks were formed from deposits that created beaches and dunes not so many years ago (geologically speaking). In fact, the layout of the rocks at the bottom reminds us of a beach with a dune system behind it.

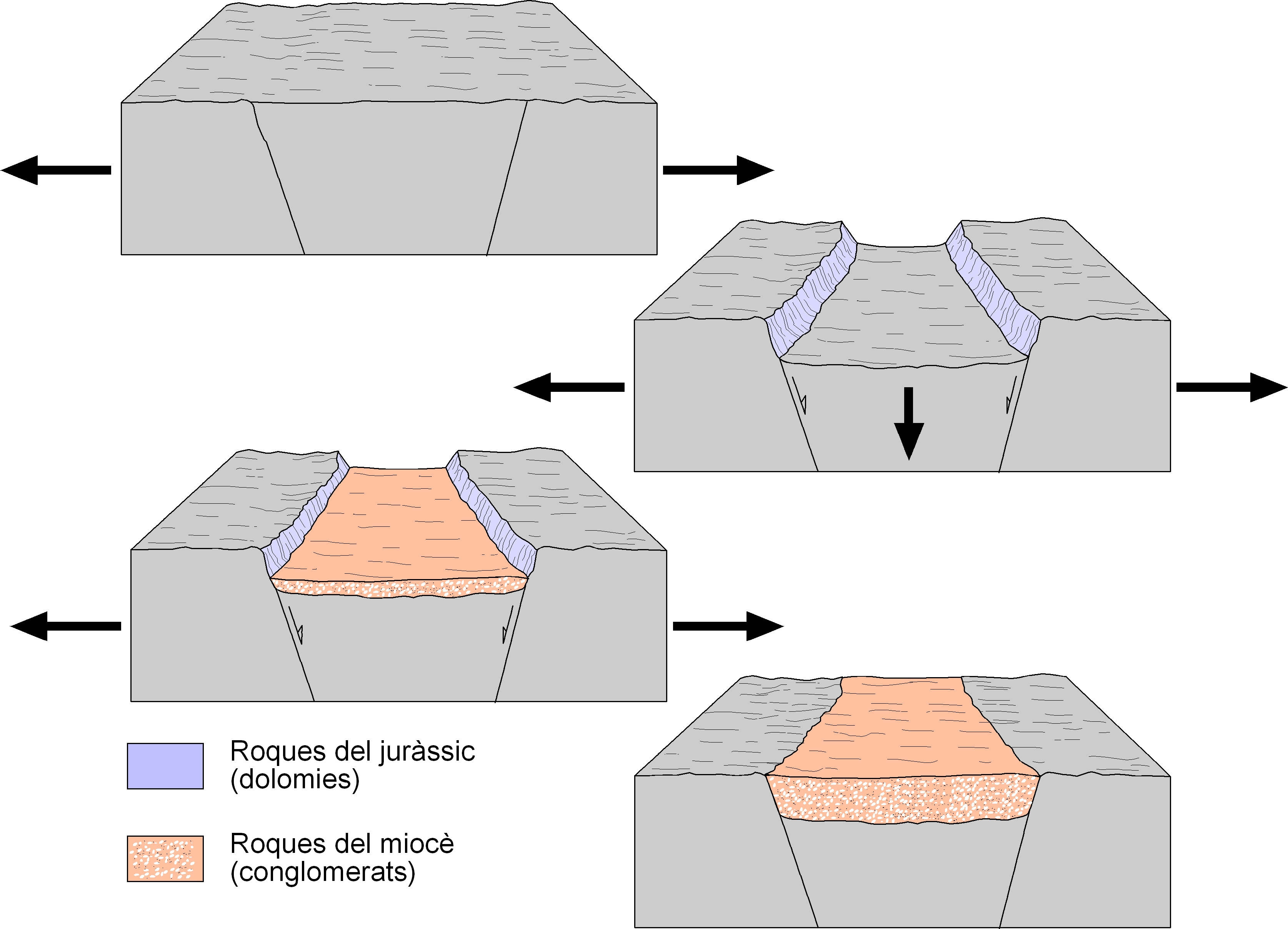

Despite their apparent relationship with the red rocks identified at the first stopping point, the rocks that you can see at the Codolar de Biniatram pebble beach were sedimented at a very different time in the geological history of Menorca. The presence of these rocks is associated with a tectonic trench, an area that sank at the Corniola cliff due to the action of faults, causing a depressed area.

We would expect that the sunken area would fill with sediments from the erosion of the surrounding grey rocks, but this is not the case. As you can see, the pebble beach is made up of fairly rounded red rocks.

Cliff at Corniola with an indication of the part that sank and subsequently refilled with red rocks (point A).

These rocks are called conglomerates and are formed from another pre-existing rock that was not round and that was displaced by streams that gave it these rounded shapes. Normally, a sedimentary rock of detritic origin (clasts larger than 2 mm).</p></div>">conglomerate is formed because a rock is transported by a river and the dragging and tumbling of the rock along the riverbed wears it down and ends up giving it this rounded shape.

Evolution of the depressed area and sedimentation of the Codolar de Biniatram pebble beach. The action of tectonic movements of distension caused the appearance of faults that sank a specific area of the Penyal de Corniola cliff, made up of rocks from the Jurassic. The gap would be filled by cobbles carried by violent streams at times of severe storms in the Miocene that would, over time, form a conglomerate.

The conglomerates at Biniatram come from the erosion of the red rocks that extend from Punta Roja d’Algaiarens as far as the area around El Pilar. This area, which was probably much more extensive towards the sea than it is now, displayed significant relief from which flowed streams that at times of great storms carried the rocks and deposited them near the coastline. These streams were catastrophic; they came from the high mountains and, as they had such a pronounced slope, could drag huge blocks of rock. when they reached the sea, they were not round, but the sea sounded them, which would explain why, although these rocks have undergone a short journey (the red rocks are much nearer), they have adopted this rounded shape due to the action of the waves, which wore them down and gave them the morphological characteristics that we can see today.

Codolar de Biniatram pebble beach, made up of large red conglomerates sedimented in the Miocene, in the foreground, with Punta Roja behind. The access path to the shingle beach from Cala Fontanelles allows us to identify two different levels of fossil dunes, with the ones above the path being older than the ones below (point A).

These rocks are the oldest Miocene sediments in Menorca and were sedimented around 15 million years ago, and consequently very far from the ages of the rocks that you have mainly seen throughout the trail. The action of these energetic streams would be cancelled out by a rise in sea level (some 11 million years ago) which would see an end to the sedimentation of the conglomerates and the start of what is today the island’s most prevalent and characteristic rock, Miocene sand-sized clasts.</p><p><br></p></div>">sandstone or marès.

We should highlight two aspects referring to the conglomerates at Biniatram: their extraordinary size and the practical absence of grey cobbles from the erosion of the dolomitic rocks of the Jurassic. This fact is especially evident when we compare them with the conglomerates at Cala Morell, which were formed under the same conditions as those at Biniatram and are smaller and have more grey cobbles.

We can associate these differences with the fact that at times of severe storms, the streams, which are short and with a steep slope, eroded the mountains near the area of Algairens-El Pilar and mapped out a route that initially passed through the Codolar Biniatramp shingle beach, where it filled the existing trench with the largest and most difficult to transport blocks. Its route carried on through Corniola, where the erosion of the slopes in this area loaded the streams with dolomite cobbles. They finally came to Cala Morell, where just like at Biniatram, the sea gave them their characteristic rounded shape. Over time, this deposit of pebbles ended up consolidating and giving rise to the conglomerates

It is possible that the conglomerates that we find at Biniatram and Cala Morell were carried by energetic streams from an area situated between Algaiarens and El Pilar. First they deposited the larger (and, therefore, heavier) red cobbles from the Triassic at Biniatram. Then they received smaller amounts of grey cobbles from the Jurassic around Corniola, and finally they reached Cala Morell, where they ended up depositing the sediments in the sea. The thick arrow shows the supposed direction of advance of the main stream (modified from Estrada and Obrador, 1998).

We should highlight that at Cala Morell, the cobbles made up of dolomites from the Jurassic are perforated. These holes were made, when the rocks were deposited, by marine animals, such as sponges or date mussels, which indicates that these rocks must have been deposited on the seabed at a shallow depth. These animals can only perforate rocks of a carbonate chemical composition, such as limestones and dolomites, which is why the sand-sized clasts.</p><p><br></p></div>">sandstone cobbles at Biniatram are not perforated.

This trail can be complemented with a visit to Cala Morell, in the area near Punta de s’Elefant, which you can get to from Biniatram along the Camí de Cavalls on a 3-km section or by going back to Algaiarens and getting there by vehicle. Besides seeing the differences between the conglomerates in the two areas, at this cove you can see the contact caused by a fault between th4e two regions into which the island is divided, the Tramuntana to the north and the Migjorn to the south. This fault at Cala Morell caused part of the grey dolomites in the Tramuntana region to sink and the gap caused to be refilled by conglomerates. One of the main differences to be stressed between the two areas is that at Cala Morell, above the red rocks, you can easily see the marès that sedimented after the conglomerates. This observation, especially evident towards the west, in the area known as Cul de sa Ferrada, allows us to identify the three principal units that make up the Menorcan Miocene series, the sedimentary rock of detritic origin (clasts larger than 2 mm).</p></div>">conglomerate lower, the middle made up predominantly of marès and the top of reef origin.