Access route to the stopping point.

A visit to Cala Morell is a ‘must’ if you want to complete a trail with the aim of getting an overview of the geological features of Menorca in just a day. Consequently, Cala Morell is one of the key sites on the island from a geological point of view. The stopping point is at the Punta de s’Elefant o des Campanar headland (at the western tip of the cove), which you can get to from Carrer d’Orió Street in the residential area.

The interest here is due partly to being able to see from here the contact between the two geological regions into which the island is divided: the Tramuntana and the Migjorn. From this point, you can very clearly see on the other side of the cove (the eastern side) how a number of reddish rocks are abruptly cut by much older grey rocks. It is interpreted that these rocks are together due to the action of a fault and represent a leap in time of some 165 million years.

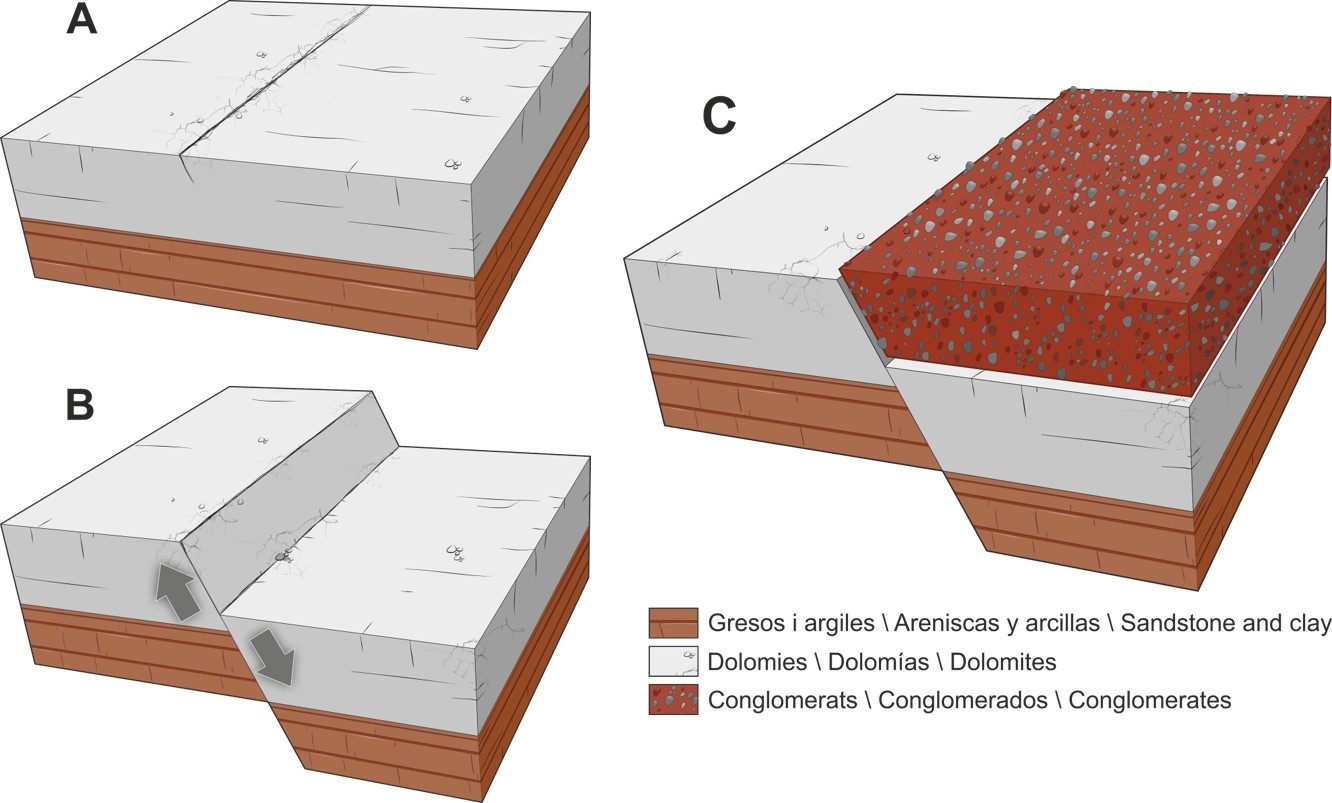

The presence of a large fracture in the grey rocks (A) caused part of them to sink (B). Subsequently, the gap resulting from this sinking would be filled by sediments of reddish colours dragged by streams (C).

The grey rocks are dolomites sedimented in the Jurassic period (some 180 million years ago) while the red ones, which are the same as the ones we are walking on at Punta de s’Elefant, are conglomerates. The sediments that caused these conglomerates were transported by streams that probably came from an area near the present-day coves at Algaiarens and Pilar around 15 million years ago. Short but very steeply sloping, these streams proved to be catastrophic. At times of severe storms, they eroded the high mountains (that existed at that time in Menorca) and could drag huge blocks of rock that were finally deposited at Cala Morell and other sites.

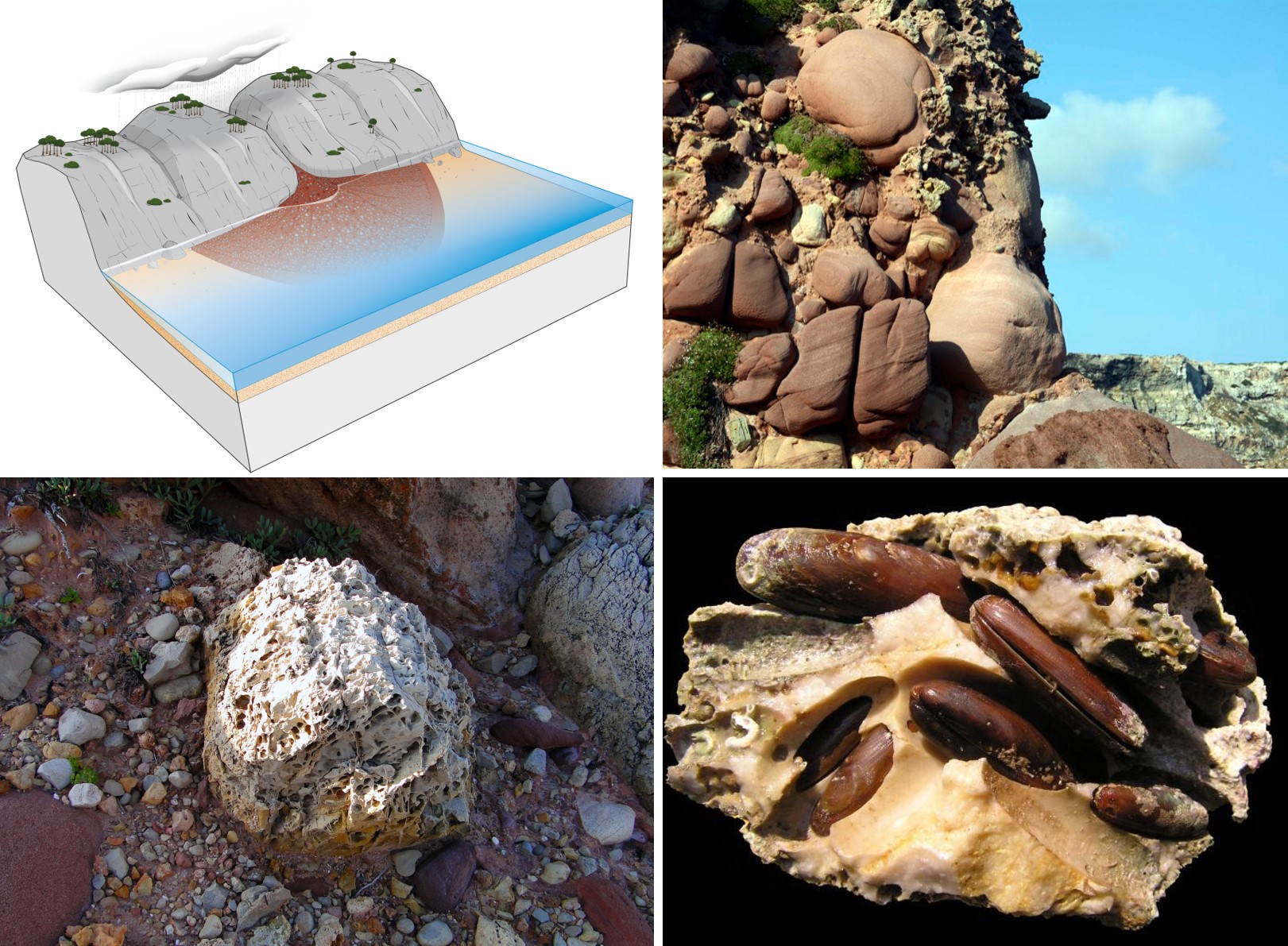

We should remember that when they reached the cove, the fragments were not round. Their transport was too short for them to have rounded enough to take on a round shape. It was the sea that tossed and turned them over and over for many years. Consequently, the tumbling of the cobbles caused by the action of the waves eroded them and gave them the rounded shapes we see today. You will see also that some of the grey cobbles are significantly holed. These holes were gouged out by lithofagous marine animals, in other words, by organisms that bored into the rocks to live there, such as present-day date mussels. All of this indicates, therefore, that when most of these rocks reached Cala Morell dragged by catastrophic streams, they must have been deposited on the seabed at a shallow depth.

Idealised reconstruction of Cala Morell in the Miocene, where large streams from the high mountains would drag along huge accumulations of sediments at times of severe rainfall. The fragments transported by these sediments would be rounded by the action of the sea (above, point A). The grey cobbles can display numerous perforations, which were made by lithofagous animals when the sediments were deposited, such as present-day date mussels, shown below (last photograph taken from https://zco1999.wordpress.com/2012/07/06).

The action of these energetic streams would be cancelled out by a rise in sea level (some 11 million years ago) which would see an end to the sedimentation of the conglomerates and the start of what is today the island’s most characteristic rock, Miocene sand-sized clasts.</p><p><br></p></div>">sandstone or marès. From Punta de s’Elefant, we can see how, on top of the red rocks, other white rocks –marès– can be identified.

View of Cala Morell with an indication of the main rocks and their age and the position of the fault. We should also highlight that near the fault contact are outcrops of the remains of an old Quaternary age beach (around 130,000 years old). This rock is marès, but it was sedimented much later than the marès of the White Menorca (Miocene) (point B).

At Cala Morell, the red-coloured conglomerates from the Miocene break away from the division of the landscape by colour introduced in this chapter, where the rocks of this age, in the Migjorn region, are associated with the White Menorca as they usually feature colourations of these tones. In fact, as has just been noted, white marès is also present in the cove, above the conglomerates and especially visible at Cul de sa Ferrada (to the west of the Punta de s’Elefant headland). In any event, this fact is a good opportunity to muse on the island’s geological variability and understand the processes that led to its rocks.