| UTM-X | UTM-Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STOP 1: PAS D’EN REVULL | |||

| STOP 2: BARRANC DES CANALÓ | |||

| STOP 3: MARÈS | |||

| STOP 4: ES TORRETÓ |

Suggested route to the stopping point.

Pas d’en Revull is a small section of the Camí Reial, an old way that crossed Menorca from one end to the other and that may have its origins in the Roman era. The initiatives of volunteers from Ferreries have managed to recover it, and it is a group of volunteers who are responsible for keeping the path in a good condition for it to be visited. From a geological point of view, Pas d’en Revull is a small tributary channel some 450 metres long that flows into Es Canaló, which is in turn a tributary of the main channel of the Barranc d'Algendar ravine.

The top part of Pas d’en Revull is an open section, protected by the rock only on the south side, and therefore exposed to the north winds. In this initial, rather rectilinear section, the rock is homogeneous and of little interest, but as you go further into the ravine, this perception changes considerably. As a result, you need to take notice of its walls, where fossils, bioturbations and evidence of the processes that configured this small ravine take on interest for the visitor curious to find out about its geology.

Initial route from Pas d’en Revull (point A) and section where the path closes in and where we suggest making the first observations along the trail (point B).

This way, just as you reach the point where Pas d’en Revull narrows considerably, by looking at the walls, you will see that they are not homogeneous but very often display a network of small tubes, which indicate the biological processes that affected the rock, at a time before it was a rock and consisted of a sandy sediment that had not yet consolidated.

Consequently, relatively frequently, you will see tubes, sometimes bifurcated and branched, built by animals that lived during the Miocene and that, in their desire to find food, shelter or escape their predators and enemies, stirred up the sediment, which would later consolidate forming a rock and creating these shapes that we associate with the process known as bioturbation or bioerosion, erosion associated with living beings.

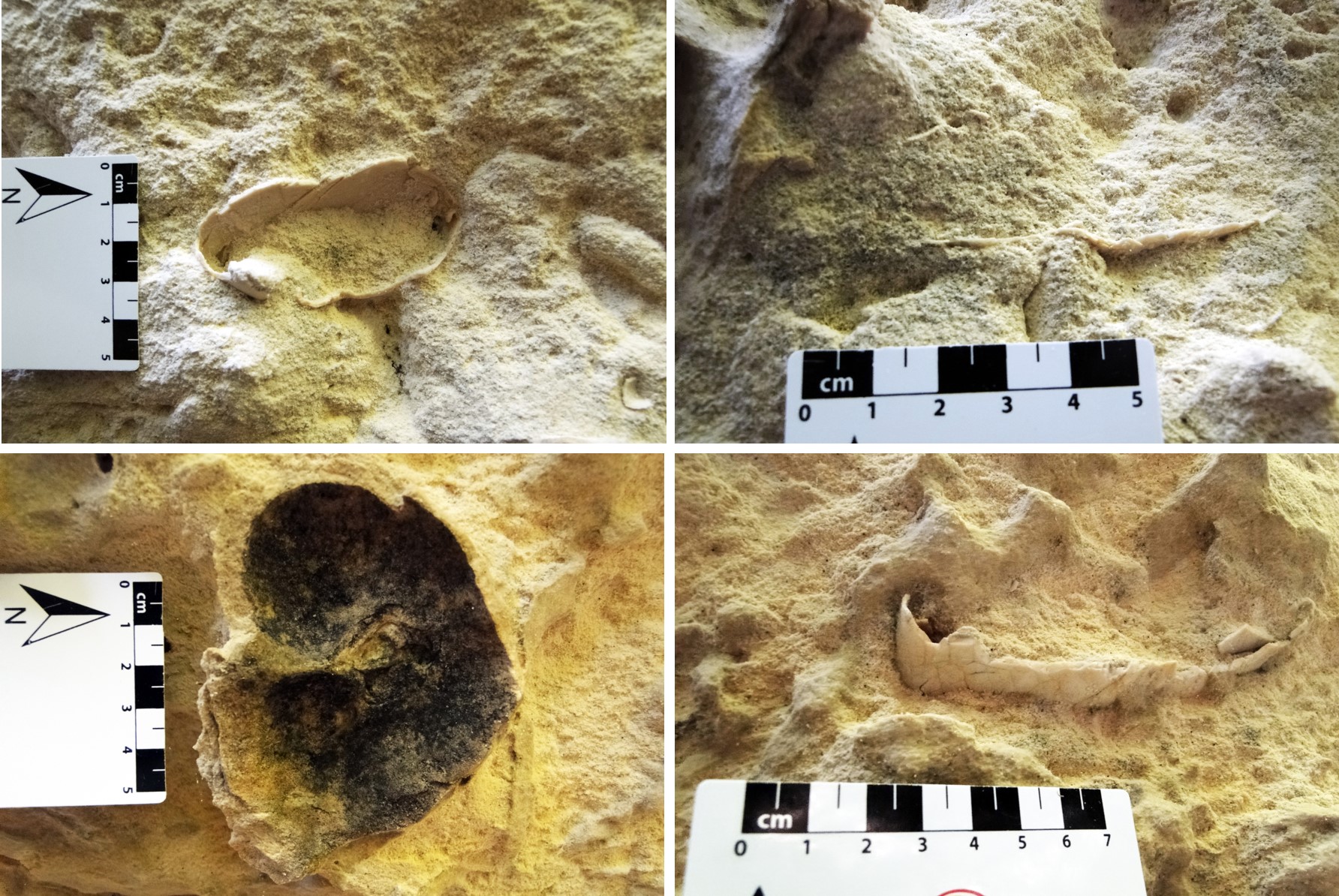

The animals responsible for these structures did not fossilise because they had no hard or skeletal parts. However, in these walls, as well as in others along Pas d’en Revull from this point on, you can identify fossils of other animals, essentially sea urchins, although also of other organisms such as clams, all of them marine organisms, which tells us therefore that the rock was formed millions of years ago in the sea.

Talus that was intensely stirred up by organisms that were alive when it was sandy sediment (above) and close-up of the tubes created as a result of this biological activity (below) (point B).

These fossils appear to be embedded in the rock. What happened is that the fossils formed as the organism was buried among the marine sediments immediately after dying, so being protected against the waves. Under these conditions, the fleshy parts decomposed and quickly disappeared; by contrast, the hard parts, such as the shells, lasted with their own geological composition or with it transformed. In some cases, these hard parts subsist almost intact (indicating a fairly non-energetic sedimentation ambience), but more frequently their pores and open spaces are partially or completely impregnated with minerals from the water that has entered the sediment and, over time, all of it turns into rock (a process known as sedimentary rock, also named lithification.</p><p><br></p></div>">diagenesis).

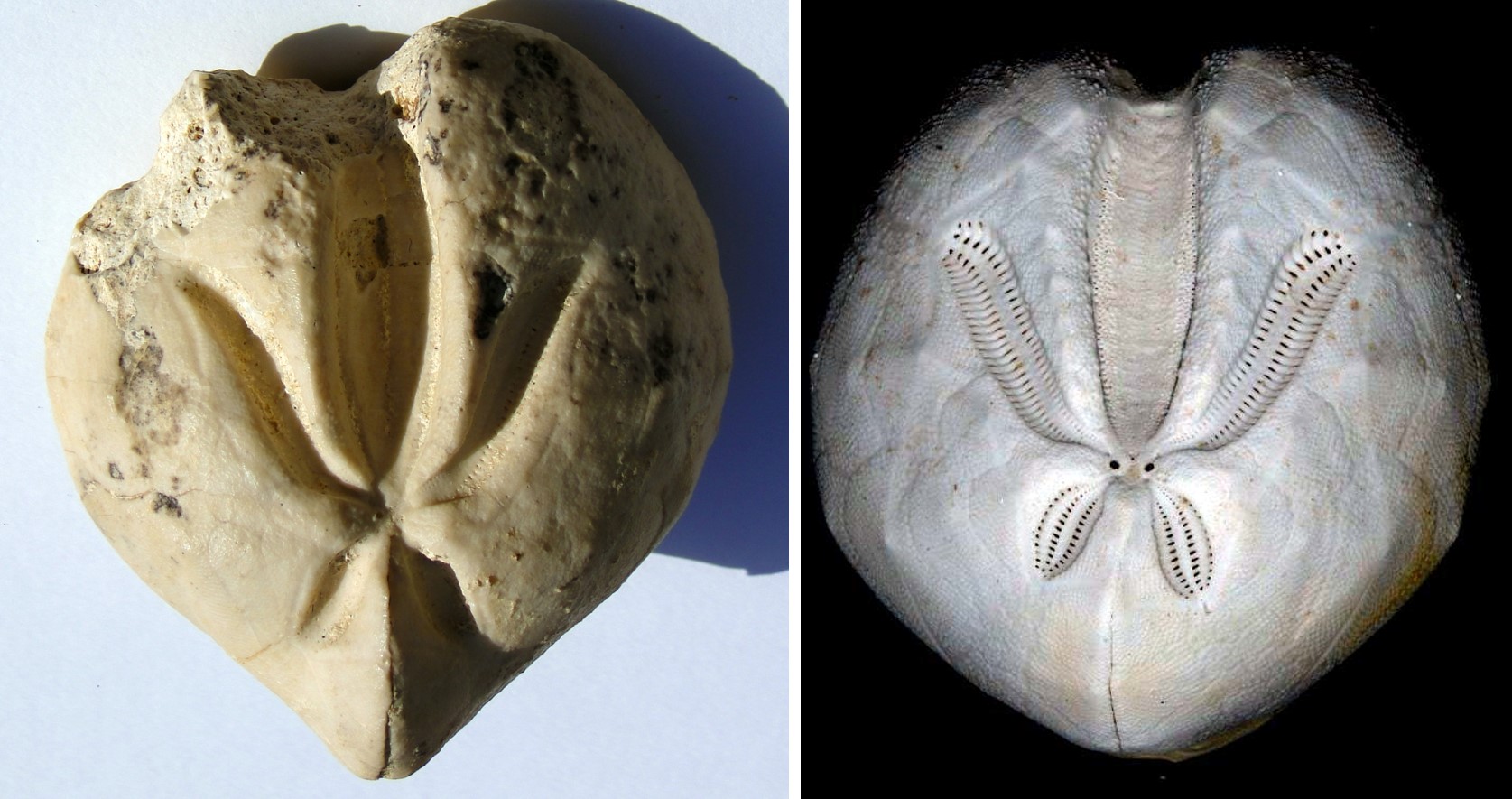

The fossils that we can identify in these rocks are of marine organisms that lived in the Mediterranean in a time period of between 5 and 11 million years, the Miocene. During this time, the Mediterranean was a warm sea similar to tropical seas today. For this reason, we find in these seas today the descendants of some of the organisms that lived in the Mediterranean during the Miocene. At Pas d’en Revull we find fossils of different species of sea urchins, both as the original shells and as moulds resulting from the sediment that filled up the empty spaces of the original shell that disappeared.

The majority of the species of sea urchins of the Miocene rocks of Menorca belong to the group of irregulars, characterised by a bilateral asymmetry and disparate body shapes (armoured, oval, long, flat, pentagonal, etc.), and consequently very different from the sea urchins that we find on our coasts today, of a subcircular convex shape and "pentaradial” symmetry.

Fossils of irregular sea urchins at Pas de’n Revull (point C).

Examples of sea urchins of the Schizasteridae family, fossil and present-day. On the left is a fossil specimen found in the Barranc d'Algendar ravine and given to the Menorca Geology Centre; on the right is a current specimen found in 2003 on a beach in New Caledonia at a depth of 5 metres (Koghisberg‘s Collections). Both specimens have a maximum diameter of 60 mm.

The small channel at Pas d’en Revull opened up due to the effect of the erosive action of water. In fact, we find a good example to imagine this process in a small meander created by water, which when descending at high speed “smashes” against the rock and diverts to continue along its course. The water erodes the rock, in this case the lower part, but its action does not end here, as it also produces an undercutting that leads to blocks falling from the higher parts, where they can cave in due to not being held in place at their base from erosion by the water course.

However, we possibly should not only associate the opening up of the channel with the erosion of surface waters but also of subterranean waters. In other words, it may be that in the past, some part of Pas d’en Revull were caves through which subterranean water flowed. This may also have eroded the rock and widened the cavities to the point where their size prevented them from supporting the land above and it caved in. A possible clue that could relate some sections of Pas d’en Revull with old caves is the presence of a red sediment that is embedded in the rock. These are very common clays in the caves that may include other angular cobbles such as the ones we see at Pas d’en Revull. In Menorca, fossilised bones have been found in this type of rock in some caves.

This red or orangeish clay is called ‘terra rossa’ or ‘residual clay’ and it is the residual material resulting from the dissolving of marès. Subterranean waters, slightly acid by reacting with the atmospheric CO2 or coming from the decomposition of plants and animals, dissolve the Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">limestone rock and deposit the clay as residual product, with iron oxides in its composition, which gives it its characteristic colour.

Undermining of the lower part of the cliff at a section of Pas de’n Revull due to the effect of surface waters and deposit of red or orangeish sediments, which is called ‘terra rossa’. This clay is the residual material that is left when subterranean waters dissolve the limestone rock (point D).