The rocks that surround the El Pilar beach, together with the relief around Punta Roja d’Algaiarens headland, constitute the best place on the island to observe the predominantly red geological series that sedimented between the late Paleozoic and the early Mesozoic (a time frame of between 255 and 240 million years ago).

Red clays and sandstones at Punta des Carregador (foreground) and Punta de l’Anticrist (background) headlands.

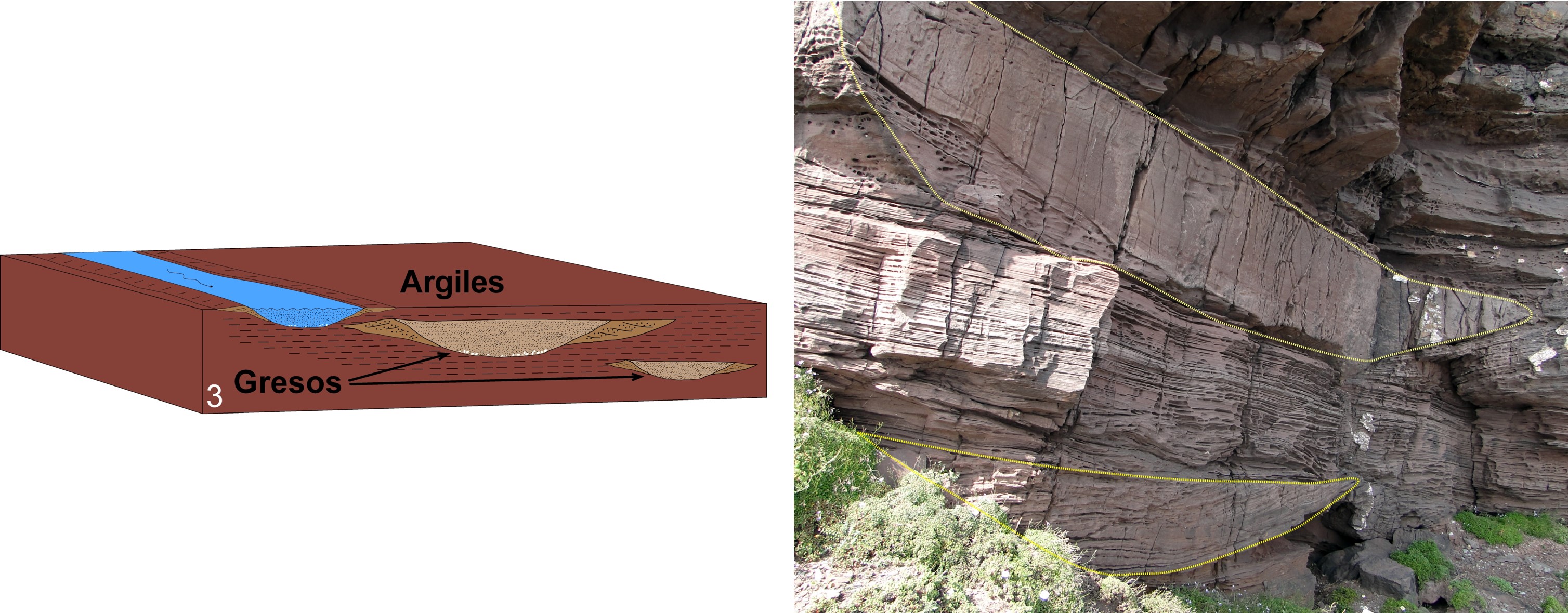

The site at El Pilar is modelled on red sandstones interleaved between clay materials. The sandstones were created by the accumulation and consolidation upriver of grains of sand that were transported by vast rivers which eroded the nearest mountains in Menorca, thrown up in the late Paleozoic, evidence of which is the dark soil that you can see on the eastern edge of the cove. The finer materials, the clays and silts, sedimented when the rivers flooded, and accumulated extensively along the banks of the river channels, on the flood plains.

At El Pilar, you can quite often see lenticular structures which are the ancient river channels that were filled in with sand. These lenticles are convex with a flat upper contact and their lower part is more or less irregular due to the effect of erosion by the river.

These rivers also dragged along cobbles that, over time, formed the rock we call sedimentary rock of detritic origin (clasts larger than 2 mm).</p></div>">conglomerate. Cobbles that therefore were created by the erosion of mountains during the Paleozoic and which are not very rounded, meaning that they were transported only a short distance. Each layer of conglomerates is the product of the sedimentation of an energetic and stormy flooding of the rivers.

At certain points of the location, such as the eastern edge of the El Pilar beach, these red rocks are covered by other much more modern rocks, with ochre colouring, that sedimented during the Quaternary, the latest of the geological periods. These rocks must have been deposited at a time when the sea level was lower than it is now, which led to an extensive surface area of sand being dragged inland by the wind until it was stopped by the first relief that bordered the coastline. Over time, this sand became consolidated, forming the rock we call marès. It is a permeable rock, which therefore allows water to flow inside it. When the water comes up against impermeable materials, such as red clay, its path is interrupted, which causes it to flow outwards in the form of an upwelling or spring. The El Pilar spring is a good example of this process.

The El Pilar spring at the eastern edge of the cliff lining the cove and close-up of the marès made from grains of sand. The upwelling is situated right at the contact between the permeable marès and the impermeable red clays.

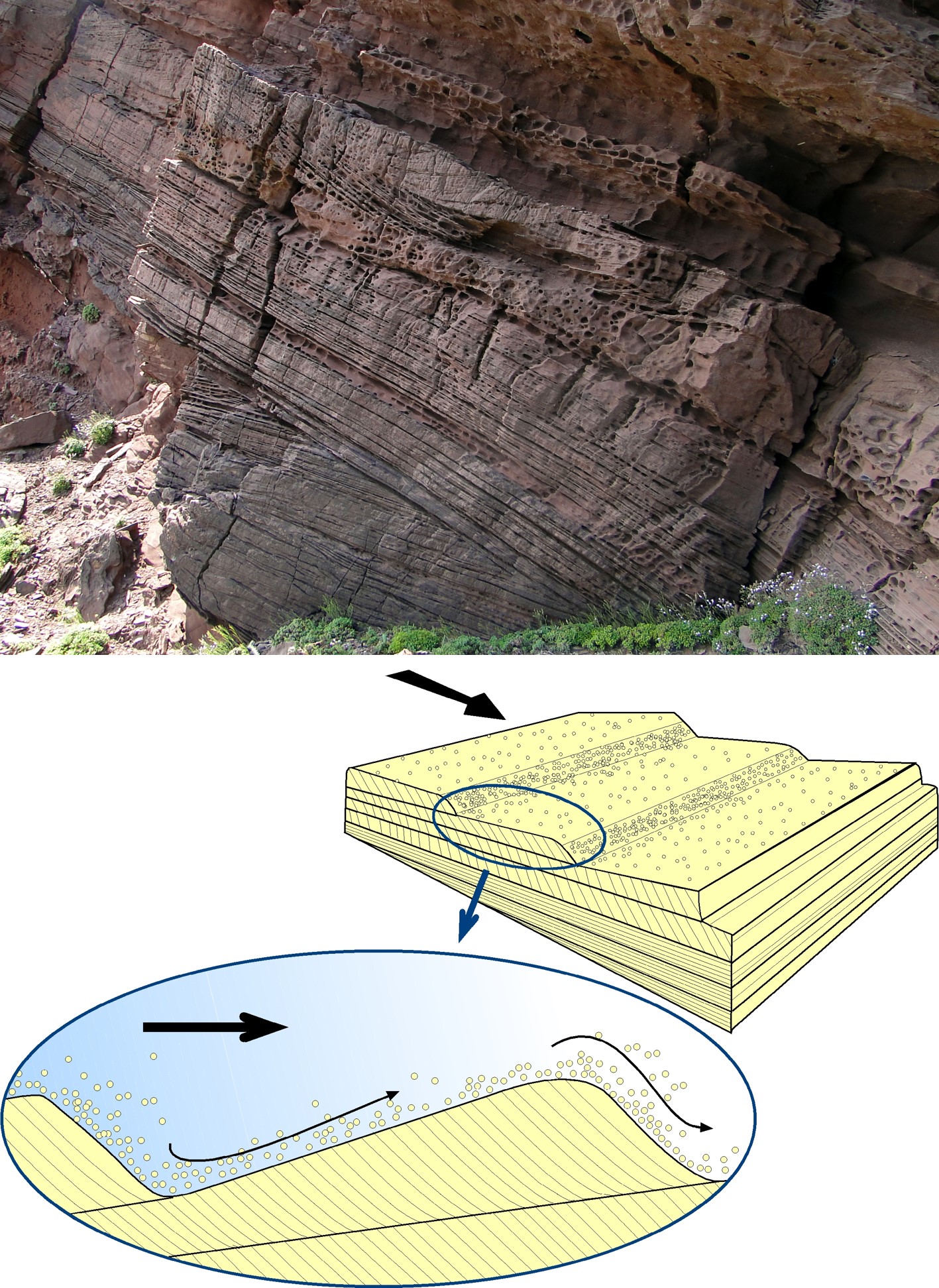

At the Macar d’Alforinet shingle beach, you can see a spectacular concentration of red pebbles from the nearest cliffs, in other words, the rocks that have fallen away in this area are rounded by the action of the rough waves swept up by the Tramuntana northern winds. Up close, you’ll see that many of them have grey lines that are sometimes inclined, which correspond to the cross stratifications of the rocks that have been conserved in the pebbles. These structures were formed because the river caused a succession of small peaks and troughs of sand when this had not yet consolidated, which give the sediments a fluted and undulating appearance. When the sediments consolidate, these forms can persist on the rocks, giving rise to fine cross-laminae in the section of the rock, which are a reflection of the types of currents that carried the grains of sand.

Cross laminations at El Pilar and diagram of their formation. The fine inclined laminae are a consequence of the sand being carried by the rivers, which led to small piles when the current was not very strong. By contrast, when the speed of the water increased, they did not form and the grains of sand ended up giving rise to lamination in parallel flat layers. Note that they are undulating shapes that slope gently on the windward side and sharply on the leeward, which enables us to determine the direction of the current.

Macar d’Alforinet shingle beach and close-up of the cross stratifications of the pebbles. They are normally large as the smaller ones have been dragged into the sea.

At the Pla de Mar cliff, we can see an old copper mine, known as the ‘Adela mine’, which was in operation between 1901 and 1904. The most common minerals identified here are chalcocite, malachite and azurite. The mineralisations are recognised especially in levels of small cobbles (microconglomerates) and are seen primarily as small lentils of chalcocite (copper sulphide) that are sometimes altered into malachite and very occasionally into azurite (copper carbonate). The mineralisations are associated with layers of coal, which cause an oxygen-poor atmosphere (reducing) that favours the deposition of minerals. The mine has two entrances and a vertical ventilation shaft next to the Camí de Cavalls path, which meet in a main L-shaped gallery some 78 metres long and 2 metres high; these considerably modest dimensions indicate that the mine did not prosper economically.

Lower entrance and vertical ventilation shaft of the Adela mine and malachite (green) and chalcocite (black - lead grey) minerals at a small slag heap in the mine.

From the Macar d’Alforinet shingle beach, we recommend continuing the visit towards the Muntanya Mala hillock or Anticrist cliff, either climbing the mountain or, especially, following the route alongside the sea. Here, you can see the contact between the materials sedimented in the late Paleozoic era (in the Permian, which dominate the relief of the area around the Cala del Pilar cove) and the early Mesozoic (from the Triassic, which make up the top part of Muntanya Mala hillock). Although the colour is more or less the same, the contact between the materials is relatively clear, as at this point, the last materials sedimented in the Paleozoic are clays and sandstones, whereas the first ones of the Mesozoic are a sedimentary rock of detritic origin (clasts larger than 2 mm).</p></div>">conglomerate with cobbles predominantly of quartz but of different colours. Consequently, we should point out that the transition between the end of the Paleozoic and the beginning of the Mesozoic did not involve a great environmental change, as sedimentation continues to be fluvial, and it is only the type of river that changes: they go from having a lot of meanders where the water ran regularly to other more rectilinear rivers that flowed fiercely in heavy rains.

Cliff at Anticrist, which rises imposingly from the coast. The cliff is fairly fractured, which causes numerous rockfalls, heightened by the flow of underground water and erosion by waves at the foot of the cliff.

Walking on the debris at the foot of the cliff, you’ll come across a superb dike of volcanic rocks, of igneous rock of maphic composition (rich in silicates of magnesium and iron and in silica) composed mainly of plagioclase and pyroxene.</p></div>">basalt composition, which slices through the rocks from the lower Triassic. The magma was injected through cracks and solidified inside the Earth while heating up the rocks through which it rose.

Dike in the lower part of the Anticrist cliff and close-up of it.