Punta Roja d’Algaiarens headland is one of the most impressive sites of geological interest in Menorca due to the erosive shapes affecting the rocks sedimented in the Triassic and that are, in turn, sliced through by a splendid dike of volcanic rock. It is also outstanding for its scientific interest as it is one of the best outcrops in Menorca for studying rocks from the lower Triassic (sedimented around 250 million years ago).

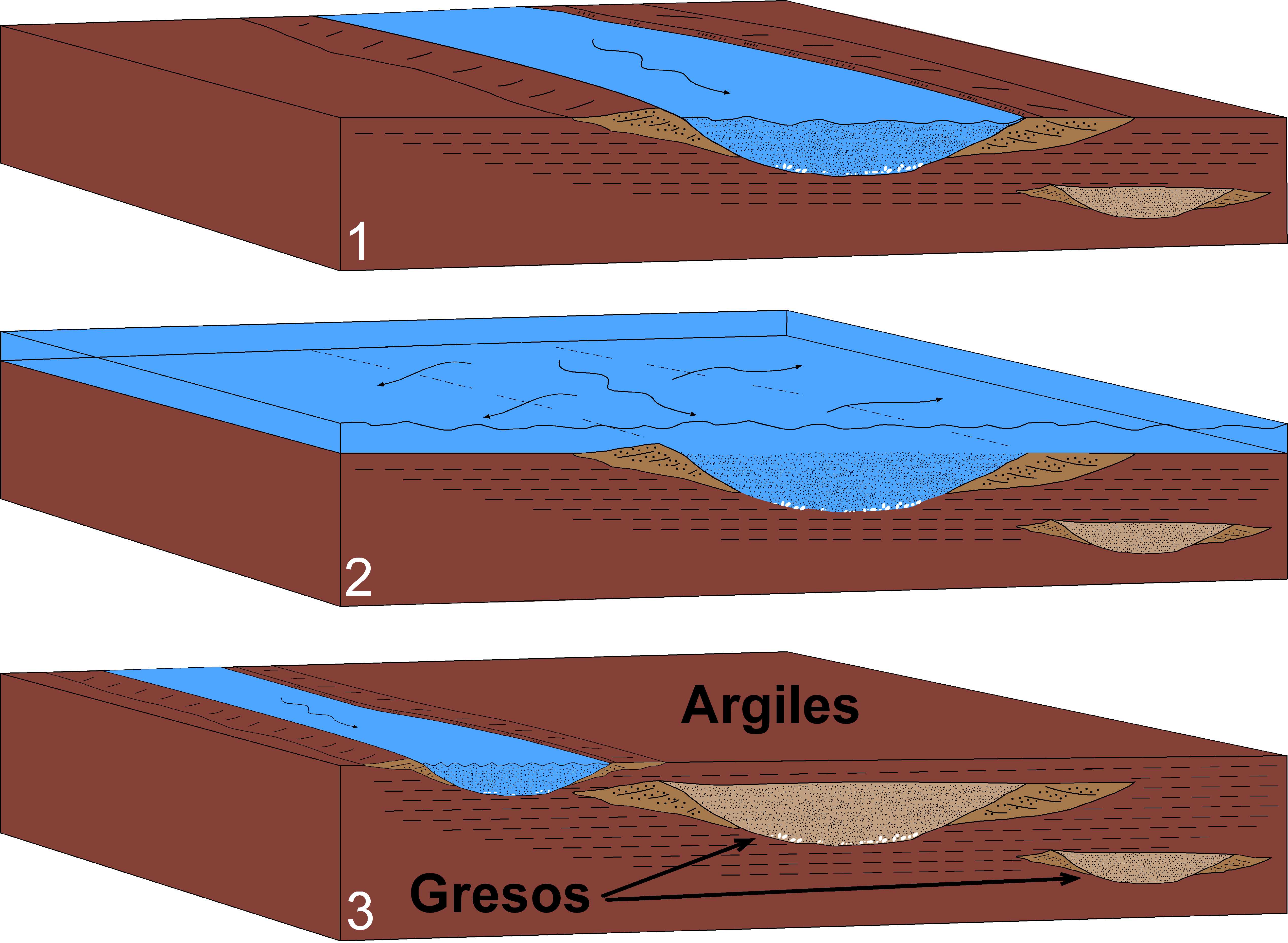

Consequently, the bottom part of the geological series, which constitutes the headland itself, is made up of a lower level of red rocks from the lower Triassic. The lowest part is made up primarily of sandstones, rocks constituted fundamentally by grains of sand, hence their name, although in Menorca they are popularly known as ‘pedra de cot’‘. This sand was transported by great rivers that eroded the nearest mountains in Menorca, thrown up in the late Paleozoic. The accumulation downriver of the grains of sand, and their consolidation, would end up creating the red sandstones. Above this, we can identify strata made up predominantly of much smaller grains than the sand grains, which are clays and silts. The rivers also transport these grains, which accumulate on their banks or flood plains when they overflow.

Sandstones are rocks made up primarily of grains of sand that were transported by very powerful rivers that eroded large mountains. The deposition of the grains of sand on the river bed and their subsequent consolidation would end up creating the red sandstones. Much smaller in size, the clays and silts accumulated on the banks of the rivers or on the flood plains when the rivers overflowed.

Numerous palaesols can be identified between the clay strata; these are “fossil” soils formed during the Triassic and preserved by the subsequent accumulation of sediments. Their presence enables us to deduce that, in the flood area, up to thousands of years could pass between periods of the rivers rising and falling as soils can only be formed during prolonged periods of no sedimentation since they need a great many years to form.

Palaeosols interleaved between the clays of the lower Triassic with whitish colourations and close-up of them. Note that as they are more resistant to erosion, they stand proud between the clays.

The presence of iron oxides dissolved in river waters stained these rocks red in the outside atmosphere (oxidising), giving them their characteristic colour. Consequently, these rocks usually adopt red colourations as very small concentrations of iron are enough to stain the rocks, although you can also see white ones, which is easily explained, as the main component of these rocks, quartz, is frequently white. These original colourations may have been preserved, for example, because sedimentation occurred in small and shallow wetlands with practically no oxygen (reducing atmosphere).

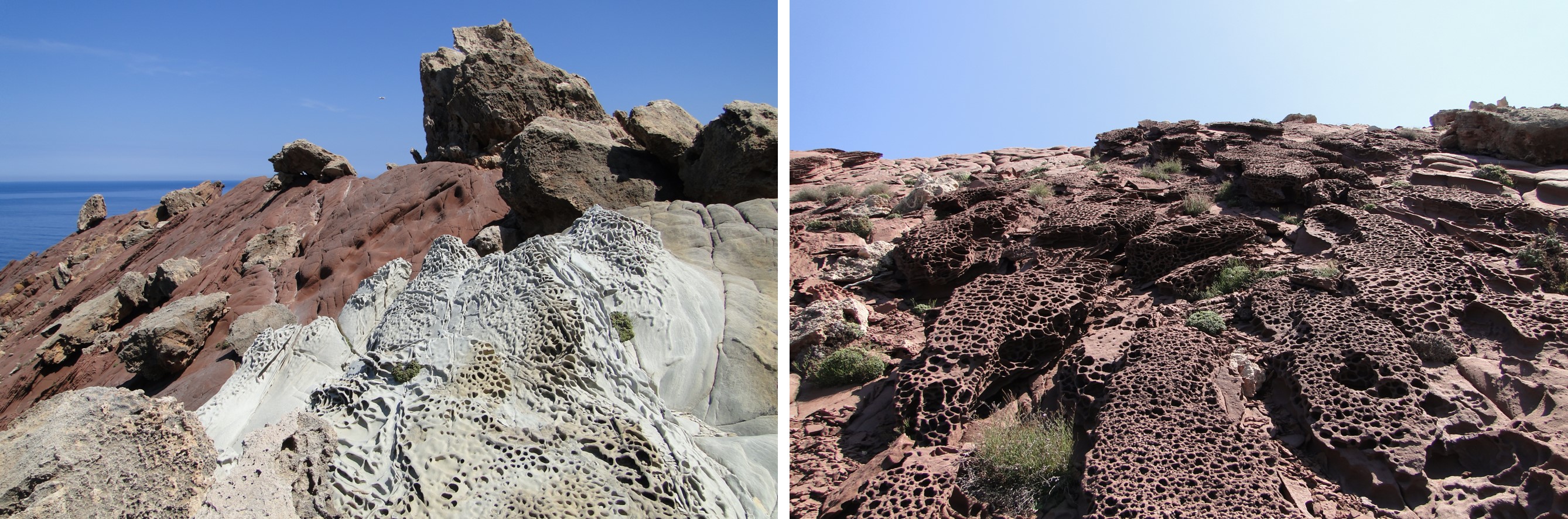

The rocks at the Punta Roja headland display an advanced state of alteration. One of the most characteristic manifestations of this alteration is so-called ‘alveolar or honeycomb erosion’, caused by the wind and abrasion by sea salt and due to the variations in the composition of the rock. In other words, the different hardnesses of the rock itself lead to the hardest parts standing proud of the softer ones, which are “decayed” by the process of erosion.

Alveolar or honeycomb erosion in both red and white sandstones is one of the characteristic features of the Punta Roja headland.

The most characteristic or unique element of the site is a dike of grey volcanic rocks with greenish tones, which slice through the red rocks in their predominantly clayey upper part. They are highly altered and are dolerite, a rock of igneous rock of maphic composition (rich in silicates of magnesium and iron and in silica) composed mainly of plagioclase and pyroxene.</p></div>">basalt composition, which cooled in the magma that caused it inside the Earth’s crust, in other words, the rock was formed from magma that opened up a path to the surface through cracks and solidified inside it.

The predominantly red series of the lower Triassic is sliced through by a dike of volcanic rock at Punta Roja. The dike is some three metres thick

From Punta Roja towards the Es Bot beach, we see a level of finely stratified grey rocks on the cliff, sedimented in the middle Triassic, so after the previous ones. They are limestones and dolomites sedimented in a calm and shallow sea. In other words, after the continental processes that caused the predominantly red series, a rise in the sea level led to a radical change in the type of sedimentation. No fossils have been identified in these rocks and their formation is attributed to the action of bacteria that caused the precipitation of the calcium carbonate that forms the rock.

Limestone and grey dolomite section from the middle Triassic situated on top of the red materials of continental origin that are identified in the foreground of the photograph.

Both the sandstones and the clays from the lower Triassic and the limestones and dolomites from the middle Triassic are abruptly sliced through by a whitish or ochreish rock that gains in top of a stratigraphical unit or stratigraphical sequence. </p></div>">thickness towards the Es Bot beach. This is a dune from the Quaternary, and therefore an accumulation of sand, dragged from the beach and deposited inland by the action of the wind and which, over time, has consolidated, giving rise to a rock that we know by the name of marès. These materials are considerably broken, which means the habitual shearing of blocks of this rock from the cliff. The presence of old soil, predominantly clayey, among the materials of the Triassic and those of the Quaternary favours these rockfalls as their easy erosion has opened up a cave, leaving the marès without any support.

Fossil dunes from the Quaternary with a horizontal layout that cut through the inclined red and grey rocks of the Triassic. A clayey soil has developed between the two materials, albeit with the presence of cobbles in some sections that give it the nature of a conglomerate. These materials erode easily, which has enabled the opening of caves, favouring the fall of the overlying materials and the tilting of the whole level with the appearance of major cracks.

The tour of the Site of Geological Interest can be completed with a visit to the Cala en Carbó cove, although due to the difficult land access, we recommend doing this from the sea. It is considered that this cove features one of the best sections of the island to view the transition from the materials of the Paleozoic (specifically, the Permian) to those of the Mesozoic (Triassic).

Cliffs from the lower Triassic that demarcate Cala en Carbó on both sides.