The coastal area that comprises the S’Algar - Alcalfar area is associated with a fossil site of brachiopods, rhodoliths (red algae), bivalves (clams), echinoderms (sea urchins) and fish teeth. Unfortunately, the presence of these fossils today is residual due to the intense fossil-hunting to which the area has been subjected. If you identify a fossil, it is very important that you do not remove it and that you leave it where it was found. They are part of the geological landscape and we should not forget that they are elements that can contain hugely important information and should not be removed from the site unless it is for scientific purposes: fossils outside their geological setting lose a lot of information. If you take them away, their worth decreases drastically, and in any case, if they have been removed, they should be left in a museum institution.

From this point of view, outstanding in the site of interest is the Es Vermell tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop, a fossil site featuring fish teeth, which have been the subject of several scientific studies. The site on fairly uneven land caused by intense karst erosion, in other words, by the dissolving of the rock by water heavy with CO2. The gaps caused by this karst phenomenon have subsequently been filled by sandstones and conglomerates, the grains and cobbles of which, derived mainly from the erosion of sandstones and sedimentary rock which tends to exfoliate in small flakes, similar to sedimentary rock formed by clay.</p></div>">pelite. </p></div>">llosella from the Paleozoic, were dragged by streams. The tectonic, eustatic or antropical processes</span></p></div>">outcrop is outstanding for its red colour, as a result of the sediment that acts as an agglutinant, in other words, as cement for these particles, being rich in iron oxides.

Es Vermell cliffs, characterised by a cement rich in iron oxides that gives the rock its characteristic red colour, which gives the place its name (‘vermell’’ means red), and the tooth of a Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1837), one of the largest sharks ever to have existed, found in this outcrop and donated to the Menorca Geology Centre.

We should highlight that the Site of Geological Interest represents a splendid place to see the border between the two upper and lower geological units that have been recognised by scientists in the Migjorn region of Menorca. Marès, the predominant rock in the region, is made up of fragments of shells of marine organisms together with sediments from the dismantling of the relief that formed Tramuntana. In any event, it should be remembered that its composition varies depending on the time and place the rock was formed, as logically, depending on these factors, the remains of the living beings that would end up constituting a large part of the rock would be different. The lower unit of the Site of Geological Interest (which is, in fact, the intermediate in Menorca’s Migjorn region), and therefore the oldest, was sedimented around 11 million years ago in a flat area inclined towards the sea depths at different depths, between 15 and 20 metres at the Site of Geological Interest. The upper part, much smaller in extent on the island, would have been deposited around 7 million years ago in an environment of reefs and in the area that concerns us here, the lower part of the photic zone, in other words, at the greatest depths still reached by light, which, in any event, had to be less than around a hundred metres. The change in sedimentation, which the passage from one unit to the other entails, is related to a change in the ecological conditions, which caused a decrease in nutrients and, therefore, an alteration of the food chain, possibly due to a climate change that went from wet to dry and also perhaps related to a fall in temperature.

At the Site of Geological Interest, the border between the two units is recognised especially by an ochreish-coloured crust made up primarily of phosphate, which outcrops spectacularly at the Punta de Rafalet headland. This crust can be related to the surface of a seabed made up of a very hard layer encrusted with phosphate (among other more scarce elements such as iron). For them to form, the interruption of sedimentation for a long time is needed, so the top part of the existing sediments hardens, creating a hardened marine surface known as ‘bentonic communities tend to settle. It is indicative of long periods of little or no sedimentation, or of the exposure of a lithified stratum after an erosive period followed by an inundation.</p><p class="ql-align-justify"><br></p></div>">hardground’. The causes of this stoppage can vary a great deal, for example, it could be due to the action of sea currents preventing the deposition of sediments.

Phosphate crust at Punta de Rafalet related to a period of little or no sedimentation and the eastern border between the two upper geological units described in the Migjorn region of Menorca.

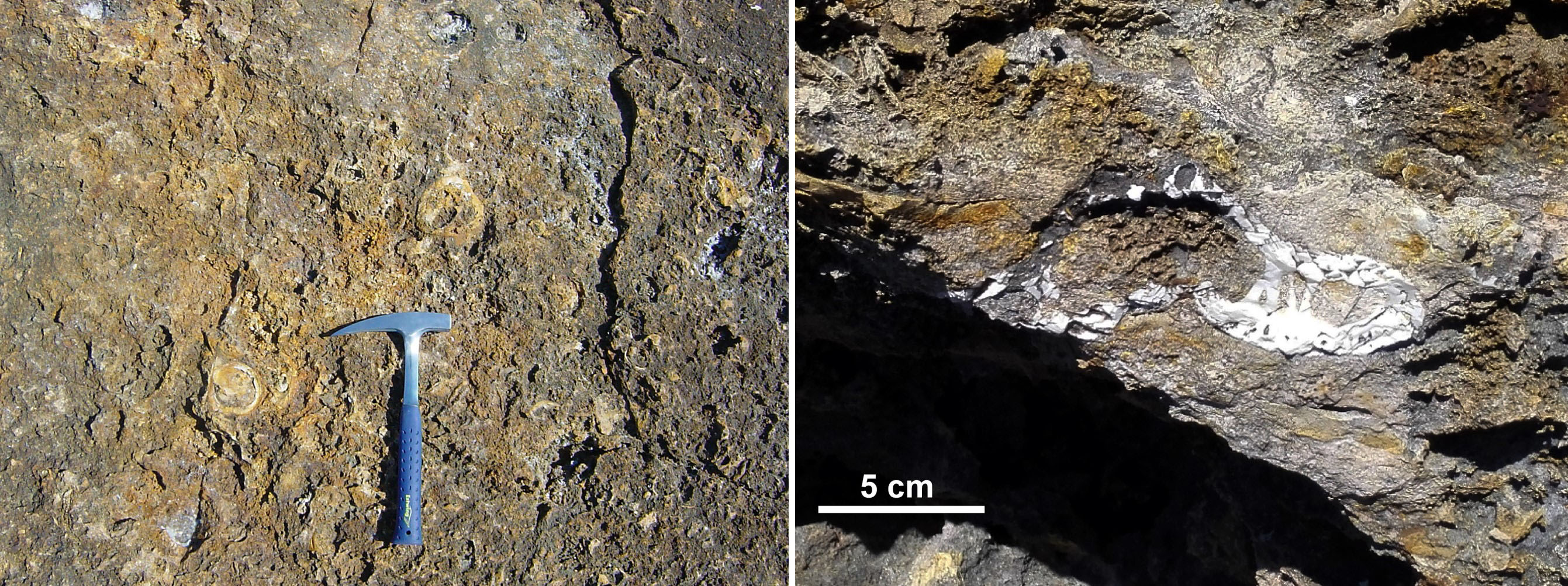

The crusts often contain unique fauna adapted to the hard surface. At S’Algar, we can discern the fossils of large clams. We also see other animal fossils, which are irregular sea urchins with a thick shell and slightly flared in shape, and red algae (rhodoliths), which constitute nodules. These two types of fossil are frequent in the sediments of the Migjorn region of Menorca.

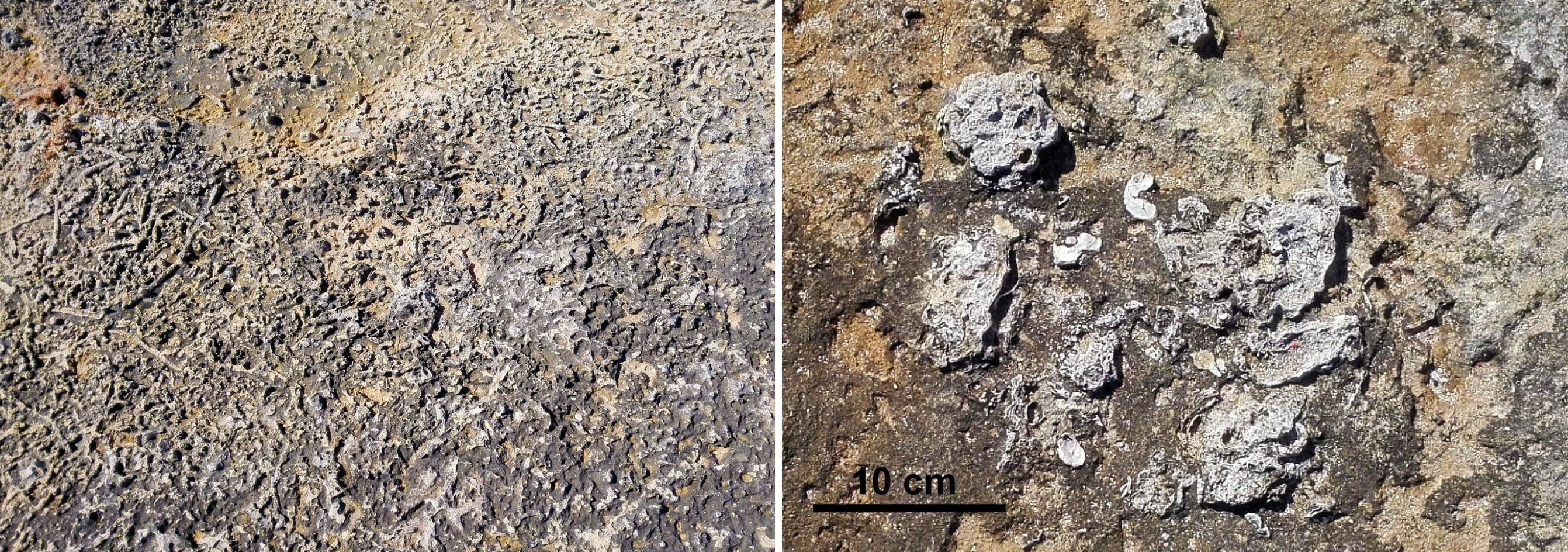

Near Alcalfar, the layers situated on top of the crust, and therefore from the upper unit, display a network of bifurcated and branched tubes, which are galleries that were excavated by crabs. These structures are called bioturbations. In some of these layers, we can identify large nodules of red algae (rhodoliths), as well as bryozoa, bivalves (especially pectinids, clams with a lower valve that is bigger than the upper one, which is almost flat) and brachiopods (marine animals with a shell made of two valves like clams, but articulated differently).

Sections of fossils of large clams on the surface of the crust and of an irregular sea urchin in the section.

Levels intensely bioturbated by crabs and red algae nodules in the layers that make up the upper unit situated on top of the phosphate crust.

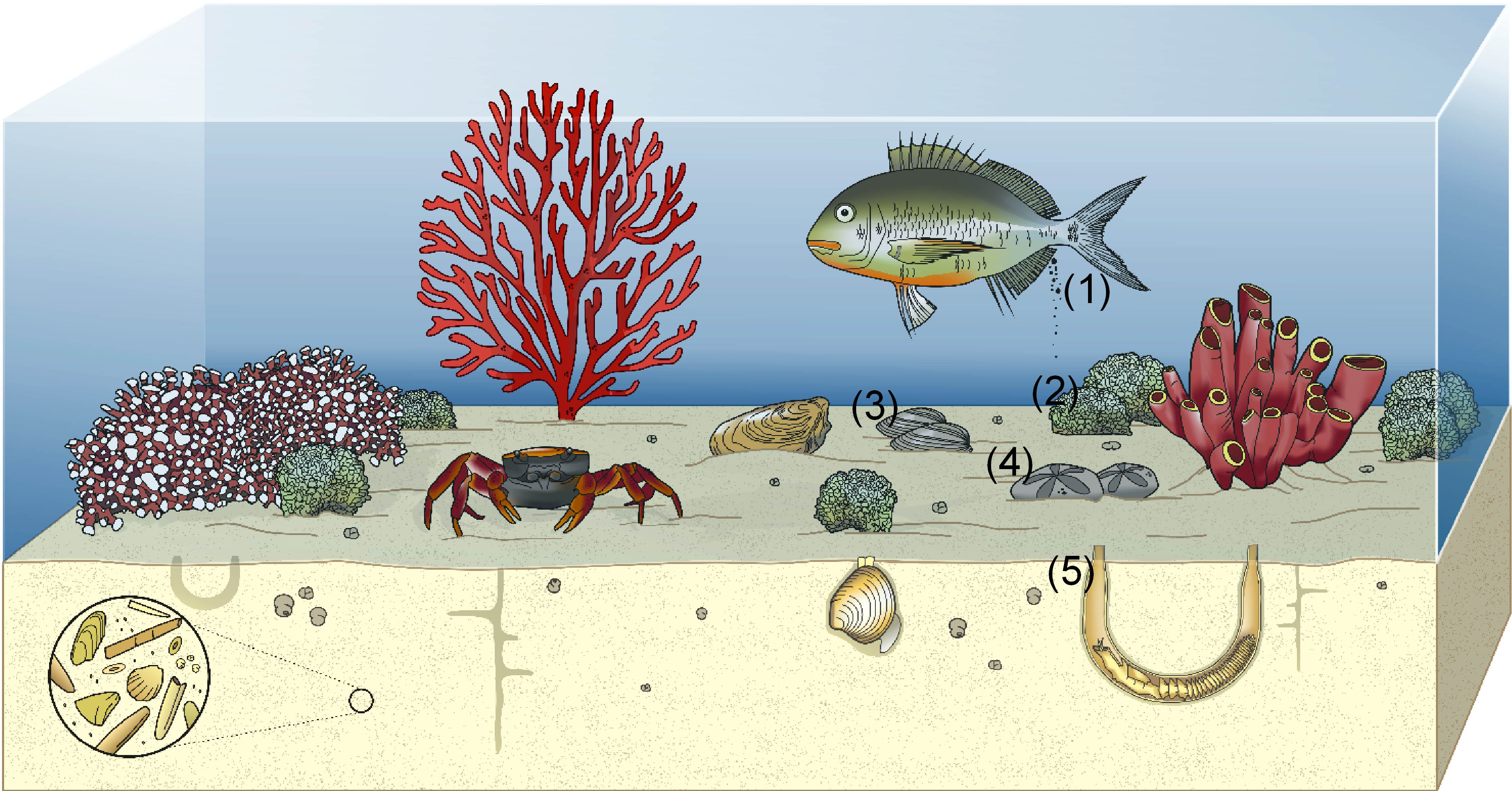

Marès is a sandy rock made up largely of skeletons and shells of organisms that have been broken by the currents, waves or by other organisms (1). Occasionally, the hard parts of these living beings were not broken and were able to fossilise, which enables us to know which living beings inhabited the sea around Menorca when these rocks were formed and, due to their abundance, which ones dominated. This would be the case of the red algae or rhodoliths (2), clams (3) and irregular sea urchins (4). Frequently, these sediments would be altered by organisms that excavated galleries that have been preserved until today (5).

These layers are intensely karstified with the development of a series of specific forms, caused by these processes of erosion and corrosion, such as the clints, which give rise to an irregular surface of sharp peaks and troughs, and caves open to the sea.

Strongly karstified thick strata, giving rise to a field of clints (and also bioturbated) at the southern end of the Cala d’Alcalfar cove.