The port of Maó is characterised by having two geologically different shores. To the north, small hills covered in vegetation offer glimpses of dark-coloured rocks from the Palaeozoic era that were sedimented around 300 million years ago. These are sandstones and lloselles that were deposited in the sea depths by currents of turbulent water. These rocks contrast with the light-coloured, horizontally-positioned marès on the southern shore, where the city was built. The marès, made from the accumulation of a huge amount of shell fragments and remains of algae, was sedimented during the Miocene, some 10 million years ago, in a warm, shallow sea. Both types of rock make contact beneath the water, which is a key factor that led to the formation of the port.

The morphology of the port can be linked to a fluvial valley that was flooded by a rise in sea level. It was formed by a stream originating in the area that is now occupied by the Vergers de Sant Joan that scoured a path through by taking advantage of the contact between the rocks; an area where the rocks are particularly weakened and where, therefore, it was easier for water to erode the rocks and advance. This stream took on huge destructive powers as a consequence of the drop in sea level that occurred worldwide (during the glacial periods), sweeping and dragging the marine rocks and sediments in the area at the time towards the great sea depths. It continued deepening and carving out a great ravine until sea levels recovered and flooded the valley that had been created, reducing the stream to a trickle. Only a few small hills that were able to withstand the erosion survived the "flooding": these are the islands in the port.

The port of Maó has two geologically different shores, to the north (on the left of the photo) are outcrops of dark rocks from the Palaeozoic, which comprise a relief of small hills. To the south (right), the light marès offers a tabular layout, which aided the establishment and development of the city.

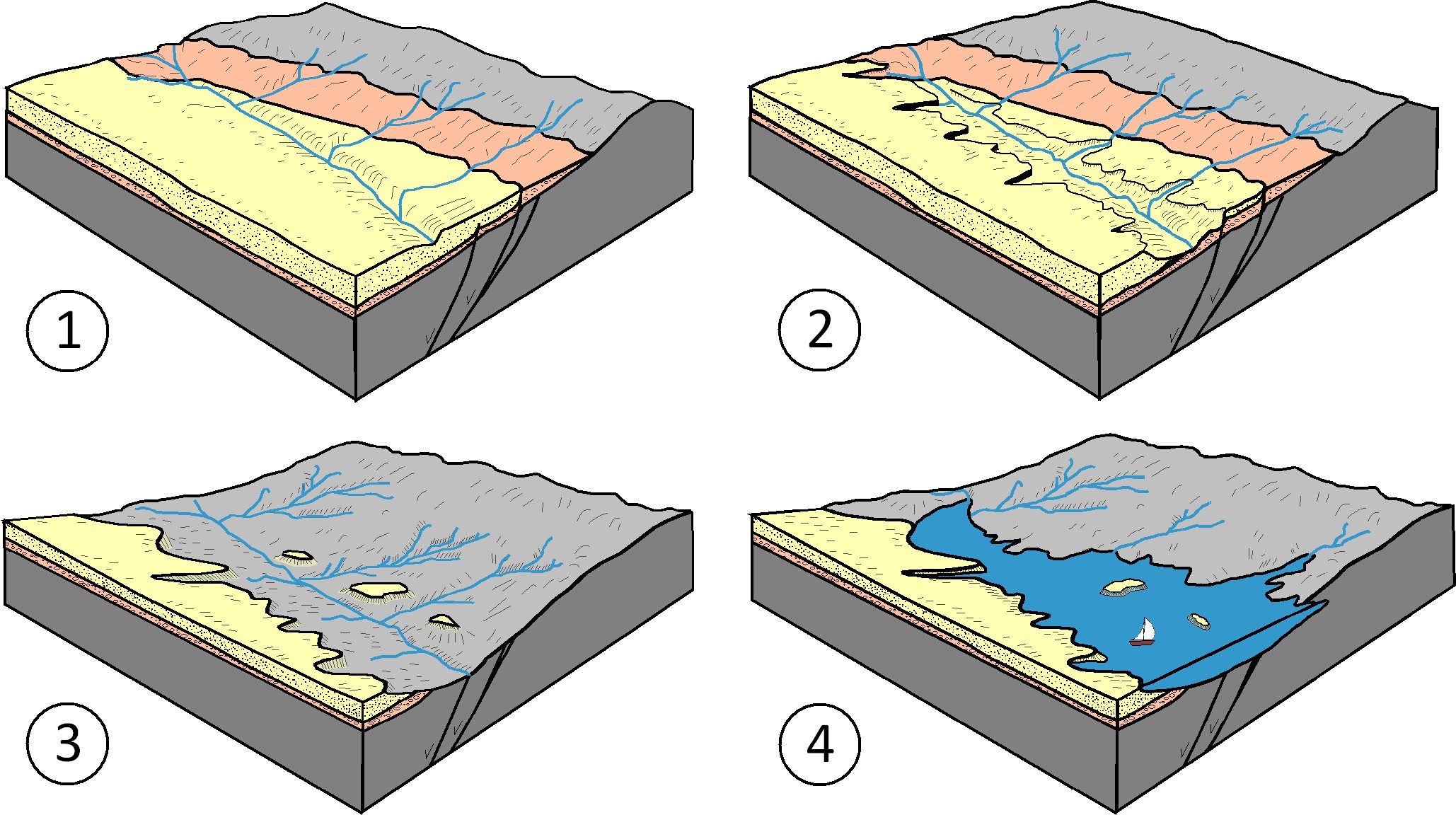

Geological evolution of the port of Maó. An ancient stream in the Sant Joan ravine opened up contact between the Palaeozoic and the Miocene rocks, an area that had been weakened due to the presence of fractures running approximately northeast to southwest, where the marès becomes wedge-shaped over the sandstones and lloselles; in other words, it is much narrower in this area (1). Later, a severe drop in sea level due to the effect of glaciation caused the slope to rise and gave the stream more power to erode with the resulting eroded and swept materials deposited in the great sea depths (these sediments now lie at a depth of between 1,500 and 2,700 metres). The southern side of the stream experienced slippages of large blocks of marès, landslides that may have caused or had a significant influence on the creation of today’s coves of Cala Figuera, Cala Corb and Cales Fons (2). The valley grew deeper and wider, forming abrupt cliffs on the southern side and a softer relief to the north, with small streams flowing between the small hills that we see on the port’s northern shore. Logically, these different morphologies were due to the different types of rock on both sides of the stream. This erosion swept away all the materials from the Miocene, except for a few small hills that would become the islands in the port (3). The rise in the earth’s temperature that caused the ice at the poles and in the mountains to melt led to a rise in sea level that stopped the destructive and erosive power of the stream, flooded its valley and consequently created the port of Maó (4) (modified from Rosell and Llompart, 2002).

However, the cliffs on the southern shore of the port not only comprise marès, but we also see limestones and conglomerates. Conglomerates are rocks formed of rounded cobbles and are always found beneath the marès, as they are the oldest. Cobbles in conglomerates, which do not have strong cement, break off easily and therefore cause the rock to be undermined at the base of the cliff. This erosion may lead to the rock on top, the marès, losing its support and consequently breaking off. This process also occurs between the marès and the Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">limestone, the weakest parts of the marès erode more easily than the harder ones, which also leads to instability that may result in blocks falling. Deterioration of the cliff, due to weathering or the circulation of subterranean water, is part of its life cycle, but it also poses a risk to residential and tertiary use of its environment, as can be seen from the constant cliff falls recorded throughout recent history. However, it should be noted that the waterproofing that the land has undergone from houses and the city’s street paving has greatly prevented rainwater from infiltrating the cliff, which has been essential in reducing the number of blocks from falling

View of the rather deteriorated cliffs in the port at Sa Costa de Ses Voltes, where a number of rock falls have been recorded and a close-up of the rocks that comprise this area, conglomerates below and more or less compact marès above.

The islands in the port have marès outcrops, but we can also see in them that they contain different and stunning contacts between the Palaeozoic and the Miocene, for both marès and conglomerates, and that these islands display interesting aspects of the geological series, as well as fossils of snails, clams and sea urchins.

Contact between the Palaeozoic and the Miocene on the Illa Plana. At the bottom, we see the sandstones with dark colourations from the Palaeozoic, above are the red Miocene conglomerates that take on these colourations due to the reddish matrix that covers the cobbles. The island is clearly crowned by a layer of marès that “flattens” the island (from where it gets its name) with gently sloping cross-lamination.

Note that the Miocene cliffs of the port and at Cala Teulera have numerous examples of fossils of an unusual type of sea urchin that has a very flat shell which is slightly convex in the middle and has very fine edges. It lived buried in the sandy seabed during the lower and middle Miocene. This is an extinct animal which is considered endemic and indigenous to the western Mediterranean and which is similar to species found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Living on the coast made it difficult to move quickly and essentially the cooling of the Mediterranean in the late Neogene and early Quaternary were probably the reasons why it became extinct.

Especially due to the effect of the waves, they are often deposited in positions that bear no relation to their position when alive (horizontally, with the broader surface in contact with the land). Also, during severe storms, these waves displaced the sea urchins slightly and in some cases moved the shells from relatively deeper positions towards the coastline. In any event, the habitat of these sea urchins was relatively shallow and their flat shape meant that they were not easily transported and prevented them from rolling away. This, together with their robust skeleton and their way of life, slightly buried beneath a layer of sand, made it highly likely that these animals would become fossilised.

The stony nature of the matrix surrounding the fossils makes it impossible to remove complete examples, which very probably helped ensure their presence today. We should not forget that fossils are exceptional geological elements that must not be extracted from the field if it is not for scientific reasons and if they are removed, they must be deposited in museums.

Fossil of a sea urchin on the Costa d’en Reynés (Amphiope bioculata DESMOULINS), and the shell of a modern species at the Menorca Geology Centre whose characteristics are very similar to that of the fossil.

The La Mola peninsula has limestones that have been sedimented in a reef of more modern materials from the Menorcan Miocene. In other words, the sediments identified predominantly on the cliffs of the port and its islands are marès, a soft rock that sedimented earlier and at a greater depth than the limestones on La Mola. In this case, the reefs formed accumulations crammed with living creatures, as well as certain green algae (Halimeda) with an algae body comprising segments that have been calcified (the process where calcium salts are concentrated in the soft biological tissue, making it harden). These concentrations crammed with living creatures would create a much softer rock than marès, a Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">limestone. The highest part of the peninsula has Quaternary dune outcrops formed by marès with fossil remains of land snails that are associated with the oldest on the island, such as the ones at Cap de Cavalleria and La Mola de Fornells.

Beneath these rocks, discordantly (in other words, through a surface that separates two sets of strata of different ages, which indicates that the deposition of sediments was not continuous), we find sandstones and lloselles from the Palaeozoic. The contact is especially interesting when viewed from the sea.

The upper part of La Mola comprises a limestone shelf from the end of the Miocene that lies on dark sandstones and lloselles from the Palaeozoic. A flat surface between both rocks indicates that the Palaeozoic relief was completely destroyed by erosion before the sedimentation of the Miocene rocks.

We should once again stress that the port has stunning examples that will help you study and understand its geological series. This is made up of Palaeozoic rocks at the base, which appear as outcrops along the northern shore, but which you can also see at several locations on the southern side. On these outcrops along the southern shore, above the dark Palaeozoic rocks, you will see conglomerates with more or less matrix, displaying a different degree of roundness and sedimented by streams during severe storms. On the very top of these rocks, which often acquire a red tone, there are very few cobbles. You will notice the conglomerates in numerous outcrops along the length of the port’s southern shore, although they are especially stunning on the Costa de Ronda.

Above this, you will see the marès, which sometimes has levels of conglomerates interleaved in the lower part, that were transported during storms by streams that flowed into the sea, where the cobbles mixed with the sand to create the marès. This sand is largely a product of the destruction of marine animal shells and algae wrought by the waves. The upper part of the marès sometimes contains layers with lots of fossils. Above, the limestones that are only found at La Mola were formed in a reef environment.