The cave of Es Pas de Vallgornera is one of Mallorca’s geological treasures, as it consists of more than 74 km of galleries, making it one of the largest caves in Spain and one of the 30 largest in the world.

In contrast with most caves, which have been known since ancient times, the cave of Es Pas de Vallgornera was discovered by chance when digging to install a well for waste water in 1968. Without a doubt, the fact of not having any natural entrance helped to keep it hidden. However, most of the discoveries of new halls and galleries have occurred during the last 20 years. It is believed that still today there are new sectors to be discovered.

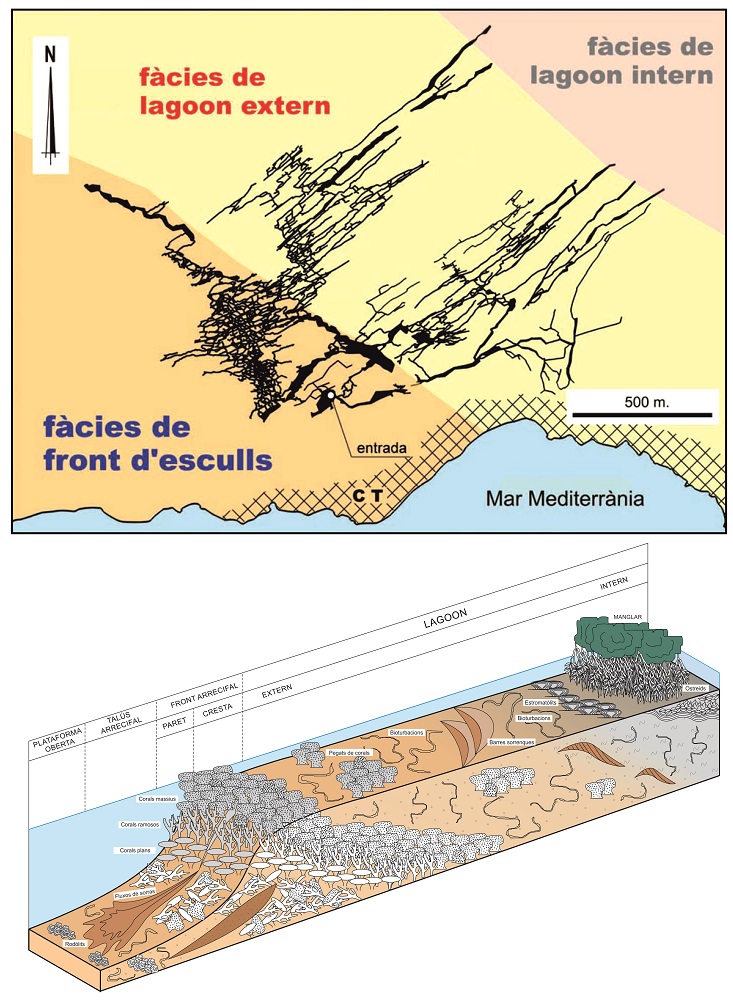

The cavity developed over one of the coral barriers that emerged in the Balearic coasts in the Upper Miocene (approximately 11-7 Ma). In this way, the various materials that compose the parts of the reef have influenced the shape of the cave.

In this respect, the reef-core stratigraphic unit and reflect the specific environmental conditions in which they were formed.</p><p><br></p></div>">facies, where there is the greatest abundance of corals (and therefore the greatest mould porosity which favours greater dissolution), coincide with maze-like zones, while the lagoon stratigraphic unit and reflect the specific environmental conditions in which they were formed.</p><p><br></p></div>">facies, where corals are scarce and fine sediments predominate, coincide with zones of scarce development, where the galleries follow fractures in the rock.

Their genesis is linked to the existence of a system of faults originating in the Upper Tertiary, which is the cause of its mainly SE-NW orientation and the ascent of hot waters from the interior of the Earth, which left their imprint on the interior of the cave.

Floor plan of the Pas de Vallgornera cave and its genetic interpretation. (modifiied from Merino et al., 2011 and based in Pomar, 1991)

As a littoral cave, over time it has been affected by the fluctuations of the sea level (eustatic changes), which has meant that today we find galleries that are aerial (above the phreatic level), aquatic (at the phreatic level) and subaquatic (below the phreatic level).

There is special interest in the saltwater-freshwater interface because it has been observed that it represents a substantial level of corrosion of the carbonates. In this interface there is an intense dissolution that widens the galleries at the point where they have remained stable for a long time. Many aerial galleries display this type of dissolution, which proves that they were formed underwater.

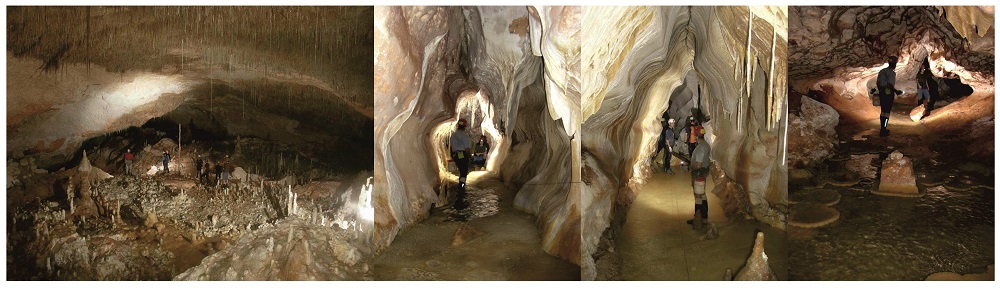

Gallery displaying the variation of the freshwater-saltwater interface in the form of two levels of dissolution.

There is a very great diversity of formations in the Pas de Vallgornera cave. In addition to the typical stalagmites, stalactites, columns, flows and flags, there are many other types like cornices, plates, coraloids and macaroni (long vertical tubes with very thin walls).

Other typical formations of this cave are phreatic speleothems, which correspond to accumulations of carbonates due to prolonged periods of stability of the sea level, which means that when dated with absolute methods they tell us about the evolution of the sea level over time.

The most peculiar formations of this cave may be the so-called ‘eccentric’ speleothems. In contrast with the common type of speleothems, which grow on a vertical axis due to gravity, the eccentrics display irregular growths that seem to defy the laws of physics. When they are very fine, like threads or roots, they are called helictites, and many of them originate from contact with a solid the free surface of the fluid ascends or descends. It depends on the surface tension and its effects are especially important in the interior of capillary tubes or between two very close-set laminas.</p></div>">capillarity processes.

Attention should also be paid to the galleries and the halls. The cave’s interior ranges from narrow dissolution galleries to large halls formed by roof collapses, notably the vast hall ‘with no name,’ 280 metres long and 50 metres wide.

Hall “with no name,” an example of a collapse hall (left), and galleries with a great variety of dissolution morphologies.

Some of the speleothems existing in the Pas de Vallgornera cave: A) Bulbs, B) Plates, C) Towers, D) Pineapples and E) Helictites.

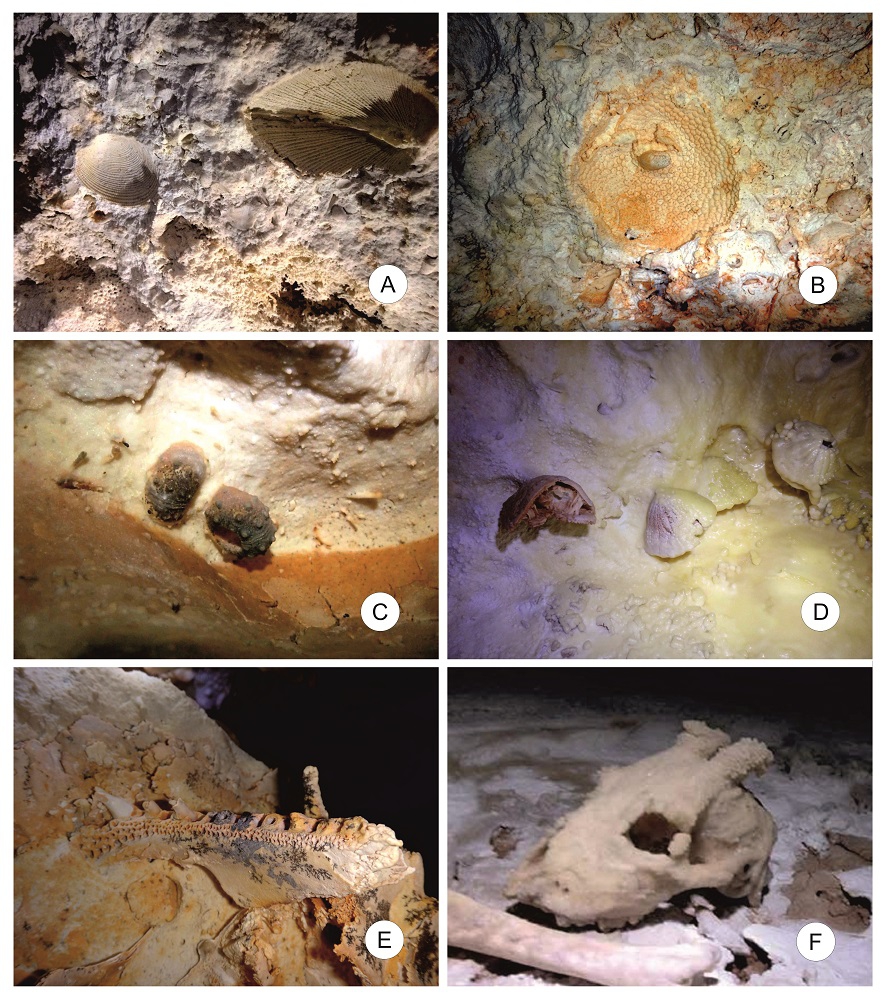

Finally, we must highlight the rich paleontological contents of the cave.

As has been commented above, the cavity developed in an ancient coral reef of the Upper Miocene which has become fossilised in the form of lumaquelic Sedimentary rock whose main component is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Its origin can be chemical, organic or detritic.</p><p><br></p></div>">limestone, which means that there is an abundance of moulds of corals, bivalves, brachiopods, gastropods and echinoderms in the walls, ceilings and floors of the galleries and halls.

Special attention should be paid to the delicacy with which the fossils emerge on the surface due to differential dissolution of the carbonates of the rock, making it possible to observe tiny details of their morphology.

The most abundant fossils correspond to the echinoderms, the most pre-eminent of which, for their size, are those of the Clypeaster genus existing at several points of the cave, which give rise to a sector of it. Much less abundant but just as spectacular are the skeletal remains of vertebrates from fishes to large marine mammals.

The cave does not contain only marine fossils, because following its formation it has served as a refuge for terrestrial animals that took advantage of ancient entryways that have now disappeared. One vestige of this is an area of the cave called the ‘Sector Tragus’ due to the great accumulation of fossilised remains of an autochthonous vertebrate of the Balearic Islands: the Myotragus.

Representative fossils of the Pas de Vallgornera cave: A) External moulds of bivalves; B) External mould of coral; C) Regular echinoderms of the Stylocidaris genus; D) Irregular echinoderms of the Clypeaster genus; E) Jaw of a barracuda-type fish; F) Skeletal remains of Myotragus.